By Amanda Dela Cruz

Editor’s note: In this issue, we are happy to publish an excerpt from Amanda dela Cruz’s award-winning MFA thesis. The thesis is a collection of five nonfiction essays, each one weaving together her life experiences and her reflections on the work of five Filipino women artists. The first part of the issue may be found here. In the continuation below, the author begins by sharing her dream of a river, connecting it to the Collective Unconscious.

Deep-dive into the Río Abajo Río

I will have to admit something to you. At some point as a feminist, I thought that there was no point for feminism anymore because feminism has found its way into our vocabulary and its ideas into our consciousness. Now, feminism has even become a brand that capitalists utilize and exploit to take advantage of the growing progressive consciousness of the middle- to upper-class generation of women. Why then is there still a need to go back to the body, one of the fundamental concerns of feminists, when we can do what we want now with our bodies?

I realized in my study of philosophy that the feminist concern for the female body is fundamental because as a woman, I am only free and safe in certain spaces of my world, but not in all the rest. You might relate with me too. One of these spaces is where I meet with my teachers, academic-friends, fellow writers, and artists to talk about, to theorize in paper, and to create refractions of the struggles of women because we have the privilege to read feminist texts that have then reshaped our consciousness.

In acknowledging my privilege to immerse myself in feminist theories, I will also have to acknowledge that I have, as Virginia Woolf called it, a room of my own to think and to write in. I now wonder if this room has a door for me to slam shut the way feminists did when they marched out of their oppressive domestication. How ironic that I am isolating myself from the world in the very space where women were once oppressed in to attain my self-actualization.

Perhaps, my words are an extension of my body that wants to obstruct the status quo. I have no theory to justify why, of all forms of art and of thinking available to me, it is in creative writing that I find euphoria and release. I think this articulation from Dr. Marjorie Evasco’s essay “The Obligations of the Writer” perfectly encapsulates this deeply personal connection between a writer and her words:

I would like to believe that we all chose to become writers motivated only by a deep need to listen to the call of words. For if we truly loved words, we would seek its music the way one who is thirsty follows the sweet sound of water. Thus, this is to be our way of being today: we are seekers of the watershed, the healing springs, the rushing falls, rivers and streams, the deep wells, the lakes and reservoirs from where our lives as writers draw sustenance.

Remember I told you that it was in a body of clear water where I saw myself naked with a pair of eyes that finally recognized my Self? But this was not a single event; I experienced this a second time when I saw my Self naked shortly after I decided to drop my MA in Art Studies at the University of the Philippines-Diliman to pursue MFA in Creative Writing instead.

I had a dream of a river beneath a river. The dream went something like this: I was naked like you, but I was squatting at the riverbank with a man dressed in khaki polo shirt, khaki shorts, and a pair of brown work-boots. He was standing on one of the rock formations. We were in an underground cave structured like a pyramid. Stalactites and stalagmites were glittering all around us. Above us was a circular bright white opening where I assumed the sunlight was coming in, but instead of projecting a ray of light from this opening, I noticed that the whole cave was illuminated by something that was coming from the depths of the river.

Something was calling me to dive deep into the clear, illuminated, turquoise river, but the man in khaki polo shirt, khaki shorts, and brown work-boots told me not to. He did not say why. His eyes were glaring at me despite the attempts of his facial muscles to pull out a friendly smile.

It was not a voice that was calling me. It was an urge coming from the depths of the river, as though there was a string pulling my soul. Dive deep, it seemed to be saying, come into the depths of the river.

I started to move my body to prepare to jump when the man in safari clothing began to move towards me. I could feel the vibration from his hushed growl that his friendly smile was attempting to conceal. He said that the river was depthless, that even if I knew how to swim I would only drown. No one had survived the depths, he warned me.

The water only continued to flow from left to right. It did not grow brighter nor dimmer, but it pulled me harder and I could feel a visceral tug in my womb.

I still wanted to dive in. I still wanted to see for myself if the river was indeed depthless. I told the man who started becoming like a hunter than a guide in the wilderness. I convinced him that water was my refuge when my world was in chaos. I trusted the river as if it was a living being. I trusted its clarity and light.

He gave a mocking laugh. Countless women had already been seduced by the river and only ended dead, he said, trying to change my mind. I could tell he was maintaining his composure, but his body started trembling as he walked more aggressively towards me, as if there was an uncontrollable mass of energy that needed to be released.

The river continued to flow from left to right exactly the way it was meant to do. The string from the depths of the river was suddenly cut and the tug in my womb stopped. Suddenly, a word surfaced in my consciousness.

Come.

I dived into the river, my hands and arms slicing the water. My urge to deep-dive felt as if I was retrieving a sapphire or an emerald that had fallen into the river. I went deeper and deeper. The voice of the man yelling for me to come back to the surface was slowly being drowned by the water. I could not tell how deep I went. My body only kept swimming to the river’s depths on its own.

Soon, I could see the riverbed. There was an opening in the middle of the vast rocky riverbed. I went there, but I could not pass through. There was a membrane that kept me from going deeper. I tried to rip it open with my hands. I even tried to pound on it out of desperation. It was then that I realized that the membrane was reflecting my naked self. I recognized a familiar expression on my face. It was the expression I had when I burned the femininity handbook.

On the other side of the membrane was another underwater ecosystem where fishes were swimming and plants were swaying with the currents. The riverbed was sliced by a horizontal line. It was a river! I had found a river beneath the river. Then, I woke up.

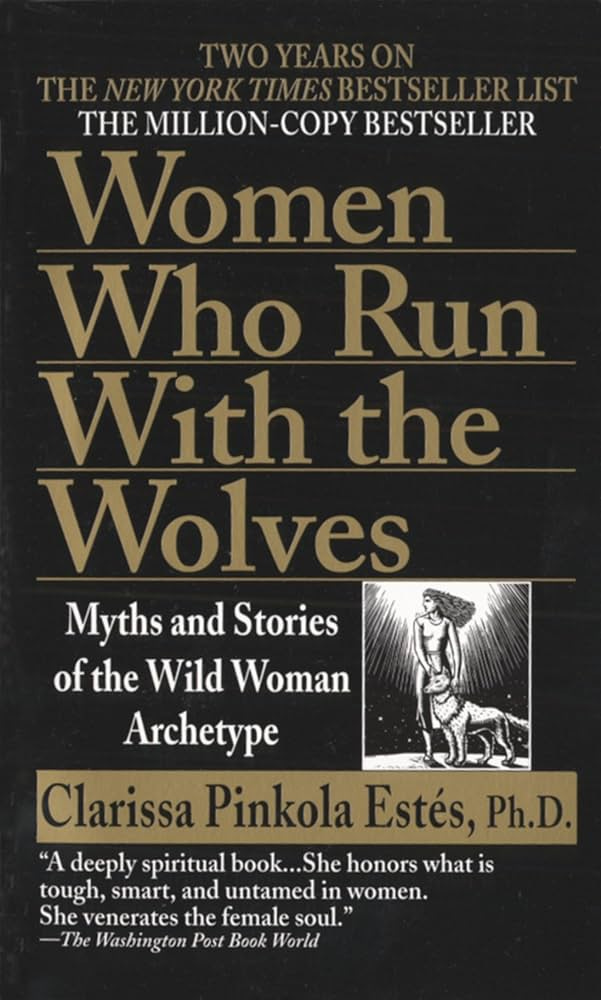

The image reminded me of the Wild Woman, the archetype of the knowing nature of women. I had read Clarissa Pinkola Estés’ book Women Who Run With the Wolves in my undergraduate years. It was a gift from Dr. Raj Mansukhani, whose classes in the Philosophy of the Unconscious and the Philosophy of Science I sat in, way before I told him, which was the first time ever I said it out loud, that I wanted to be a writer. Estés introduced the image of the Río Abajo Río or “the creative force [that] flows over the terrain of our psyches looking for the natural hollows, the arroyos, the channels that exist in us.”

When I woke up, my head had never been clearer. It was as clear as the river in my dream. I knew I wanted to write. I had to write. The dream was an affirmation that writing was a calling, a vocation, a purpose, a tool, an activism, whatever it is called that my wise knowing Self wanted me to materialize in my waking life. Could it be Cixious telling me to “Write your self. Your body must be heard. Only then will the immense resources of the unconscious spring forth”?

Allow me to take a few steps back to make things clearer. I left the Art Studies program because while I have a fondness for the visual arts, my short stay in U.P. affirmed my love for words. I never dreamed of becoming a writer. I was the only one in the family who read books for leisure, spending thousands in Scholastic Book Fairs from grade school to high school, and adding a few books to my shelf every now and then in college. But I was afraid to weave words together because I was afraid of speaking. I had stage fright, if that was what it was called. I always associated speaking with writing because these two skills are sewn together by words.

My junior in the Philosophy undergraduate program, Paul Reganit, who was in the U.P. College of Law the same time I was in the university and who later joined the student publication, introduced me to his fraternity brothers, Jayson Edward San Juan and Redbert Maines, who were the editor-in-chief and the managing editor respectively of the Philippine Collegian. They were looking for writers for the Kultura section. I was jobless then since I was focusing on my graduate studies. The meager stipend from this writing stint would provide me with finances to go around museums and galleries, and to buy books. My undergraduate thesis, a sex-positive feminist defense of BDSM, had just been published in Philosophia: International Journal of Philosophy, something I never expected because I doubted my skills for articulating ideas. I convinced myself that having my thesis published was a stepping stone towards writing in the general sense. After all, I could quit my writing stint in the Philippine Collegian if I did not like it. As expected, my essays for the student publication were mostly academic in tone and feminist in stance.

I was particularly fond of the essays penned by my colleague in the publication, Nicky Solis. He was fearless in using the personal “I” in his essays without making it sound “too personal,” I thought. This “I” navigated the themes assigned to us by our section editors, Rachelle Batan and Ian Tayona—themes of space, environment, consent, and mental health among others. His “I” words were beautifully written, far from the academic tone I was trained to write in in my undergraduate years, in which I could no longer feel my “I” and my body in the philosophical texts I needed to consume and to produce.

The river beneath the river had begun singing its song to mesmerize me. It was in a tune that only my wise knowing Self could hear. I went back to DLSU to apply for the Creative Writing program. The application documents sat on my desk for weeks until that night I dreamed of myself naked, and in spite of the dire warning of the man in khaki, I managed to dive into the river and see the river beneath the river. It was indeed Cixous telling me to write! She said, “[You] must write [your] self, because this is the invention of a new insurgent which, when the moment of [your] liberation has come, will allow [you] to carry out the indispensable ruptures and transformations in [your] history.” Waking up the next morning with such clarity, I emailed my application documents to the admission office. I had finally reconstituted the riverbed on which my Río Abajo Río could exist so my creative force could flow.

Women and the Artistic Pose

Despite of my exposure to visual art in my Art Studies program, it was only in the Creative Writing program when it sank into me that how women were posed in art remains a problematic issue which needs to be addressed. Allow me to share with you some instances from my writing workshop classes in graduate school: I once close-read a rough draft metacritically labelled by the author who was a man as a “creative nonfiction” work. However, there were two points of view—the husband’s (read: the author) and his wife’s—both of which were in first-person narration as parallel narratives. The wife-narrator was posed by the husband-writer as a martyr—one who is willing to sacrifice her relationship with her family because of her love for her husband, who chases his dream to become a writer. In return, she is thanked for for these actions by her husband-writer.

While I understood that it was a piece meant to honor the writer’s wife, my immediate thoughts were: Why label the work "creative nonfiction?” How could the husband-writer claim veridicality and give justice to the clearly invented wife-narrator? While the writer’s intention was to experiment on the limitations and possibilities of creative nonfiction narratives, given that it is fiction-under-oath, I felt it was not ethical for this writer to write a first-person narrative posing as his wife.

Assuming that the wife’s narration was based on the series of conversations he had with her, this would still amount to what is called “hearsay” and would not be admissible as personal truth based on personal experience. I remember having difficulty trusting the wife’s first-person narrative because, in the end, only the husband-writer wrote the piece using his point-of-view, even for his wife's story.

Another literary work was a play written by another writer who was also a man in which two women characters perfectly and theatrically donned themselves according to stereotypes of a may-asim-ka-pa character and a manang character. As stereotypes, their dialogue was replete with clichés. I commended the playwright’s response to my feminist criticism of his work, but I was aghast that men in my class hailed the work as Virgin Labfest-worthy. This play was not the first attempt of the writer to pen from a woman point-of-view. He attempted to write a short romance story with a woman narrator who was out of touch with a woman’s real lived experience, as evidenced in the way she thought, moved, and spoke. I do not intend to argue that there are no more women who act in stereotypical ways. My problem is when stereotypes are considered viable dramatis persona. I remember our professor in Fiction Writing Workshop, Dr. Genevieve Asenjo, affirming what I had in mind: that the execution of the writer's work did not demonstrate enough knowledge of the woman experience for him to write effectively from a woman’s point of view.

These critical problems are not only because of the gaps in actual empirical experiences of the aforementioned man writers, but also because of their limited awareness of feminist discourses. However, this is not only isolated to man writers. In one of my poetry workshop sessions under Dr. Marjorie Evasco, the class close-read a woman’s work meant to allude to the Gospel story of Jesus’ visit to the home of Martha and Mary. In the poem, the rabbi questions Martha’s worrisome attitude towards preparing a feast. The persona then shifts to Martha as she answers with a complaint about her sister, Mary, who was only sitting by Jesus’s feet listening to Him preach. The Martha-persona posed herself as if she was trying to get the attention of Jesus from Mary and she's described as feeling “coy” about the situation.

From a feminist point-of-view, it was asked why Martha feels “coy.” Was this an effort to allure Jesus? Why do women like this character in the poem desire the attention of a man? The poet objected to this reading by saying that it was not her intention to write a feminist poem. But one could not help but look at the work written by a woman with a woman character from a feminist lens.

However, I am not free from these limitations of the imagination. I, already schooled in feminism, am not saying that all the techniques of positing female characters in my literary works survived feminist criticism. I once submitted an attempt of writing an erotic poem of a young woman’s sexual rendezvous, thinking that my female persona had liberated her body from societal conservative expectations. But my language was critiqued as pornographic and objectifying, and that the persona had not liberated herself yet because she hushes the reader from telling her mother about her nights with different men. If she was indeed liberated, she would have to neither prove nor conceal her liberation from anyone anymore.

My first attempt in writing a short story fell short also, almost for the same reasons. This experience proved to me that knowing theory is a different skill from embodying feminist ideas into literary works. I am sharing with you these anecdotes from my workshop classes instead of discussing published literary texts because these writing practices are time-stamped, to show that even until now, how the woman is posed remains an issue among emerging writers amidst critical efforts pushing for progressive consciousness.

These anecdotes also show that having one’s piece workshopped is one way of addressing these issues of genre and critical orientation. With the help of constructive critiques from feminist writers, thinkers, mentors, and friends, I was able to sharpen my skill in constructing the female-narrator in my creative works. I acknowledge, however, that like in any other craft, my skills need to be sharpened continuously, throughout my lifework, my art practice.

To be continued.

Link to first of three parts

Link to last of three parts

About the author

Amanda Dela Cruz has a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing from De La Salle University, where she also earned her Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy. Since 2021, she has been writing about artists and art exhibitions for Art+ Magazine, as well as taking on coffee table book projects on arts and culture, such as Pamana ng Buhay: A Living Heritage of Biñan and an ongoing one on the legacy of the Benitez family. Her article “Unbuckling the Shackles: A Sex-Positive Feminist Defense of BDSM” was published in the open-access journal Philosophia Vol. 19, no. 2 (May 2018).