By Amanda Dela Cruz

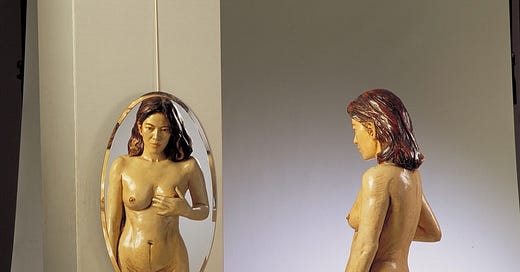

Editor’s note: In this issue, we are happy to publish an excerpt from Amanda dela Cruz’s award-winning MFA thesis. The thesis is a collection of five nonfiction essays, each one weaving together her life experiences and her reflections on the work of five Filipino women artists. The excerpt itself begins by addressing the artist Julie Lluch’s 1988 terracota sculpture entitled Thinking Nude, on display at the Singapore Art Museum, which in turn is a feminist riposte to Auguste Rodin’s famous bronze sculpture, The Thinker.

“Because so few women have as yet won back their body. Women must write through their bodies, they must invent the impregnable language that will wreck partitions, classes and rhetorics, regulations and codes, they must submerge, cut through, get beyond the ultimate reserve-discourse, including the one that laughs at the very idea of pronouncing the word ‘silence,’ the one that, aiming for the impossible, stops short before the word ‘impossible’ and writes it as ‘the end.’”

—Hélène Cixous, The Laugh of the Medusa

“The exhilarating experience of selfhood, like a foretaste of power, leads the new woman toward self-definition. Know thyself, didn’t an old wise Greek say? And having strengthened resolve in her soul by liberating herself from self-imposed psychological prisons of guilt, powerlessness, childish dependency and loneliness, she must now begin to accept herself, her body, with renewed awareness and enjoyment. The new woman now begins to know pleasure without so much guilt. She shifts attention to herself without self-recriminations of selfishness and self-love. She must take active part in production and development and support herself economically and emotionally. She must make herself free enough to be interested in ideas and people as well as national and planetary issues. She must strive to be physically stronger, more creative, and sexually potent. She must be happier, angrier, self-actualizing, more confident, moral.”

—Julie Lluch, The Making of a Feminist

There you are with your bare back towards me, facing your oval mirror. Motionless. Are you still breathing, or have you turned back into a terracotta sculpture?

Listen, I am here. Am I prying into your privacy?

You are still. Your hair that rests just above your shoulders does not move an inch. It covers your face and I need to take a few steps towards your left. Hair now tucked behind your ear.

Do you hear me? Do you hear my breath? My steps? My gasp as I see the scar on your abdomen?

I try to meet your eyes through the oval mirror, but yours are looking somewhere else. At your body. At your nakedness. At your breasts as your right hand gently presses against the softness of your full right breast. Your eyes look pensive. Your gaze is pregnant with recollection. Contemplation. The folds in your skin from both sides of your nose to the corners of your mouth deepen as you watch your hand touching your nakedness.

Is it your first time to meet your Self?

Do you remember how you got that scar on your abdomen? My mother has a vertical scar too like the one you have from below your navel down to your upper pubis. That was where I came from when my mother gave birth to me in 1995, while you were born out of a creative concept of Julie Lluch in 1988. You see, art is born out of a creative concept; a political, social, or cultural situation; a prosaic sentence or a poetic line; or a metaphor, the way I am breathing life to you into this essay. We were born seven years apart and in completely different ways of birthing labor yet there seems to be no distance between us.

I know that look you have on your face. It is the look that says, “Oh, I am here.” Yes, here I am sharing that look of self-recognition. How did you lose yourself?

Eve in the Garden of Eden

I remember when my fifth grade Sibika at Kultura teacher in St. Theresa’s College, a Catholic school exclusive for girls, told us in class, “Huwag niyong ipapakita ang katawan niyo sa kung kani-kanino,” that moment was my awakening, akin to Eve’s after eating of the forbidden fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. I was suddenly aware of my nakedness!

This teacher told us furthermore not to let our mothers see our bodies anymore and gave us a sort of script on what to say if our mothers would insist in saying that it is okay for them to see us naked because they are our mothers. We were not little girls anymore, the teacher said, and so we should take care of the “sanctity” of our bodies. Even our doctors must not see our bodies unless it is the only choice there is.

Hearing her words again now, I hear a brothel madam instead of a teacher when she said that my body only belonged to the man who would be my husband, and only he should see my naked body. “We’ve been turned away from our bodies,” Hélène Cixous said in her essay The Laugh of the Medusa, “shamefully taught to ignore them, to strike them with that stupid sexual modesty; we’ve been victims to the old fool’s game: each one will love the other sex. I’ll give you your body and you’ll give me mine” (885). Would my husband surrender his body to me the way I was taught to surrender mine to him?

As a kid, I used to feel nothing when I looked at myself naked in a mirror. I was just my body with no clothes on. These were my breasts and I never really cared if they would grow voluptuous like the breasts of females I see on TV. This was my vagina—or my vulva, as I learned later, which contained my urethra—where I peed. I had legs and feet that allowed me to move around, and my arms and hands for holding and manipulating things. I had my back to support me and my buttocks so I could sit.

What was the big deal about being naked?

This innocence was replaced by shame when I took that bite of the fruit from the forbidden tree. I was made to think that I should feel guilty because I was born with a female body. I was made to believe that my body was meant to be looked at, to be touched, to be desired, to be owned by someone else.

I wonder why it was guilt that I felt. Perhaps I felt sorry for myself. It was as if I was remorseful because I didn’t know that a man was given the privilege to take possession of my body. Thinking about it then made me want to run back to my mother’s arms and stay safe in her embrace. I am not trying to say that I felt I would be unsafe with my future husband, if ever I get married, but the idea of being owned by another never sounded right to my ears.

Since then, I always made sure no one would see my body. I avoided clothes accentuating and exposing parts of the female body that the camera often devours whenever the scene in a film or a television series would turn sexy. Oh, god! Even the tucking of hair to one side exposing the shoulder could turn into a way of seduction, if one really sexualized the female body.

When alone, I felt like someone all-seeing was watching me taking a bath and getting dressed. I always had the urge to grab my towel to cover my exposed body, the way Eve must have grabbed the biggest leaves to cover hers when she realized her nakedness and felt shame for the first time. That was probably my way of protecting myself from the fate I was made to believe in. Soon, I realized that I could not look at my body as mine in the mirror anymore. As my own body became estranged from me, my gaze became estranged too. I did not realize how quickly I saw my body as another’s possession. Maybe that is why there is a pang of jealousy from my end not only for how you look but also how you touch your naked body.

When my niece was born in 2021––the first time I experienced holding a baby—it dawned on me that the female body is policed from birth. “Huwag kang bumukaka! Kababae mong tao!” my sister-in-law and the baby-sitter would scold my two-year old niece to make her put her legs close together. They would hold her legs to stop her from taking a position deemed indecent for an adult woman to make, when in reality she was just a toddler hugging her knees to her chest so she could grab her feet. If, a big if, I were to have a child, I would take her curiosity over her own body as a milestone to celebrate, instead of telling her what not to do with her body. She is owning her body, as she should.

Do you think my mother scolded me, too, when I grabbed my feet with my hands and held them aloft when I was two years old?

Like my niece, my body felt as if it never really belonged to me too. Tie your hair. Do not cut your hair short. (It was against the rules stipulated in the student handbook.) No wearing of makeup. No sleeveless tops. Plunging necklines are indecent. Do not expose your belly. Do not expose your back. No shorts. Wear bottoms that cover your thighs. No loud laughing. (My best friend back then who was boisterously laughing, and I who was shushing her, were apprehended by the discipline officer who threatened to report us to our mothers for unruly behavior.) Laugh only a little. No melodramatic crying in public. Cry only when no one is looking. No getting enraged over something. Maintain your composure at all times. Do not make big movements. Keep your arms at your sides. Keep your knees together. Keep your hands on your lap. Keep your ankles crossed. Feet flat on the floor.

I recall these dos and don’ts as audio vignettes that automatically play until now whenever my attention shifts to my body movements. I cannot help but remember the passage from Iris Marion Young’s essay Throwing Like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment Motility and Spatiality:

Women in sexist society are physically handicapped. Insofar as we learn to live out our existence in accordance with the definition that patriarchal culture assigns to us, we are physically inhibited, confined, positioned, and objectified. As lived bodies we are not open and unambiguous transcendences which move out to master a world that belongs to us, a world constituted by our own intentions and projections (152).

Imagine, my school even required us to keep the handbook on how to be a lady! It was distributed during our Technology and Livelihood Education class, which was more like a class on domestication to me, in which we were taught how to cook meals, set the table, and operate a sewing machine. Although these are things that everyone, women and men, must learn, the class felt wrong to me because I was not offered any other choice like carpentry when I wanted to build something. The handbook was a lime-green pocketbook. I wonder why they did not use pink? Its title, written in cursive font, looked like the fonts used in the covers of Precious Heart Romances pocketbooks, in invitation cards for weddings and debutante balls, and in table d’hôte for multi-course dining. This all happened only in the 2000s.

It was only in my college years from 2013 to 2017 as a Philosophy major in De La Salle University when I learned that “female” is a category of biological sex in relation to one’s reproductive system, while “woman” is a category of gender or the socially and culturally constructed roles formed over several generations imposed on females. As Simone de Beauvoir famously said in her ground-breaking philosophical work The Second Sex, “One is not born, but rather becomes a woman” (283). This statement, especially her distinction between sex and gender, resonated throughout the history of feminist and queer theories from which Judith Butler

built her highly-complex philosophical work Gender Trouble. She proposed the concept of performativity. Agreeing with de Beauvoir’s claim, gender for Butler is something that is done by people and not something they were born as. A gender identity is created through the repetition of one’s actions, presentation of themselves, and behavior. Opposing de Beauvoir’s idea of sex as something innate, Butler argues that sex is as much socially constructed as gender. We see it only as female and male when there are intersex people who undergo surgeries to identify themselves with the medical designations that are bound in language describing one’s reproductive organs. These designations are loomed over by what it means to be feminine or masculine. Quoting Butler, “If the immutable character of sex is contested, perhaps this construct called ‘sex’ is as culturally constructed as gender; indeed, perhaps it was always already gender, with the consequence that the distinction between sex and gender turn out to be no distinction at all.”

I also learned about the problems of body image and the concept of beauty, the fight for body autonomy from societal and political restraints, the unshackling of oneself from things women were told they could not do only because of their being a woman, the physiological wonders and the limitations of the female body, and how all these are part of reclaiming the power of women. Power does not mean to reign above other sexes and genders, but simply the agency of women to reclaim what was stolen from them so they could reach their full potential.

Learning about my personal power was like burning the femininity handbook and throwing its ashes into a clear body of water where I recognized myself in my naked form for the first time since my awakening in my fifth-grade teacher’s version of the Garden of Eden. I no longer looked at my body with shameful eyes, but with the look that you have now in the mirror reflecting on your naked body.

To be continued.

Link to second of three parts

Link to last of three parts

About the author

Amanda Dela Cruz has a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing from De La Salle University, where she also earned her Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy. Since 2021, she has been writing about artists and art exhibitions for Art+ Magazine, as well as taking on coffee table book projects on arts and culture, such as Pamana ng Buhay: A Living Heritage of Biñan and an ongoing one on the legacy of the Benitez family. Her article “Unbuckling the Shackles: A Sex-Positive Feminist Defense of BDSM” was published in the open-access journal Philosophia Vol. 19, no. 2 (May 2018).