By Amanda Dela Cruz

Editor’s note: In this issue, we are happy to publish an excerpt from Amanda dela Cruz’s award-winning MFA thesis. The thesis is a collection of five nonfiction essays, each one weaving together her life experiences and her reflections on the work of five Filipino women artists. Here are the first and second parts of the issue. In the concluding part below, the author continues the story of her philosophical and artistic influences, especially her “feminist foremothers” in the course of her writer’s journey.

Feminist Foremothers

I always have the image in mind of myself naked, sitting on the shoulders of my feminist foremothers who are also naked and are sitting on the shoulders of their feminist foremothers who are also naked and are sitting on the shoulders of their feminist foremothers ad infinitum. It almost feels as if they are carrying me on their shoulders to reach what the feminist movement is set to reach the same way I will carry on my shoulders the future generation of feminists. Other times, like this one when I am engaging in my own form with works of my feminist foremothers, like the woman who created you using the warmth of her hands, feels like I am bringing them, their ideas, and their struggles as much as their joys again into this world. I imagine the feminist sitting on my shoulders giving birth to me, to my works, and to my lived experiences again when she unearths the story of her kind.

One of the women I imagine to be in my ancestry is Dr. Marjorie Evasco who I owe the sharpening of my feminist thinking, reading, and writing to. She was my professor in three of my courses in the Creative Writing program: Poetry Writing Workshop, in which my attempt to write an erotic poem, which I just told you about, did not succeed; Creative Nonfiction Techniques to which I owe my insights about the craft techniques which I use in this essay in the metaphor of undressing and inventing a mirror to look into one’s self; and Pathography, which showed me the haunting fragility yet beautiful resilience of the human body. Another thing I owe her for was her encouragement to pursue feminist literary works if this was where my consciousness was, despite the flourishing of feminist writing in Philippine literature. It meant there were things that still bothered me that could be bothering other women too, she told me in class although I cannot remember if it was in Poetry or in Creative Nonfiction. As Cixous had said, “In woman, personal history blends together with the history of all women, as well as national and world history” (882). Fast forward to my final year in the program, she has helped me in her capacity as my mentor to sharpen my skills in my ekphrastic engagement with visual works by women artists.

Dr. Leslie dela Cruz too is one of the women who I owe my formative years as a feminist to for she was my mentor in my undergraduate thesis. I was surprised to find myself taking the same path she had chosen—from finding joy in doing philosophy, to advocating for women’s place in the intellectual realm, to seeking for a sense of wholeness in creative writing. I wished I had Feminist Philosophy back in college. I am certain that if that was the case, I would have two courses that I would truly enjoy because the only course in the program that made me feel something different from the sense of uncertainty for my existence was her class on Existentialism and Phenomenology. Finally, I was able to place myself in the philosophical texts as a human that not only thinks and rationalizes, but as a human who feels and experiences things. It was a philosophy that was no longer detached from concrete human experience but draws from and philosophizes on the concrete human experiences themselves. In class, we discussed Fyodor Dostoevsky and Franz Kafka alongside other philosophers and philosopher- writers. She asked us to read literary texts that allowed me to experience Literature in a very different way—one that allowed me to experience the power of a literary text as a philosophical work. Not all philosophical works are literary; but all good literary works are philosophical.

While Simone de Beauvoir was not part of the syllabus, it was Dr. Les who introduced me to the very first feminist philosopher that I knew.

Please allow me to sidetrack only a bit for men may have an influence on a feminist writer too. There may not be men in my image of my feminist ancestors, but the world has men in it too. I owe my love for going-back-to-the-things-themselves to the Phenomenology workshop that Dr. Leslie organized, in which she invited Dr. Raj to facilitate. I remember Dr. Raj placing a matchbox on the teacher’s desk and asking us to write on a sheet of paper how we were experiencing the matchbox. Many of us used labels to describe the matchbox, but he asked us to get rid of the labels and to go back to the very experience. How were we experiencing the matchbox? He mentioned a few examples that sounded like an adult teaching a child the basic things about the world. I need to raise this love for going-back-to-the-things-themselves because this was my way of learning the phenomenological and literary way of thinking, which greatly helped me write my dream of the Río Abajo Río and the experiences of the “I” in this collection. How was the “I” experiencing the world?

Another woman in my ancestry who I believe prompted me to have a feminist eye for looking at visual arts is Prof. Portia Placino from my Art History course during my brief stay in U.P. While we had no engagement outside of class, her writings in various platforms continue to inform me how to look at art historically, theoretically, and critically. Her preoccupation in her art writing positions contemporary art in a society that continues to oppress who it can oppress. She introduced me to various readings on Philippine feminist art. It is for this reason that in this poetics essay, I choose not to be any of the many naked females in Benedicto Cabrera’s Erotica Gallery. I am neither the female caught in the act of lifting her shirt over her head, face covered, unaware of the viewer, nor the female passively lying on her side naked with her back against the viewer while they ogle her buttocks. I choose not to be the female who is reduced to her torso in Hernando R. Ocampo’s untitled series of abstractions of the naked female form in which the female figure is faceless.

I choose to be you. In this essay, I am composing my “I” standing with my bare back towards the reader. Motionless, but still breathing. From the mirror, I can see figures moving behind me, but I could not care less. I am still and so is my hair tucked behind one ear. I can hear people breathing life into their own bodies, moving around me at their own pace, and gasping as they see the scars in my body revealing in different forms the traumas my body had gone through. I do not wish to meet their eyes through the mirror, but I let them look at me. Look at me looking at my body, unclothed for my hand to explore, to identify, to familiarize with. Trace with their eyes where my hand is moving. It is moving across the mountains and the valleys of my body as if my hand had been there before. Come. Closer. Look at my eyes defining and recognizing myself, contemplating as the folds in my skin from the sides of my nose to the corners of my mouth intensify.

The Thinking Nude

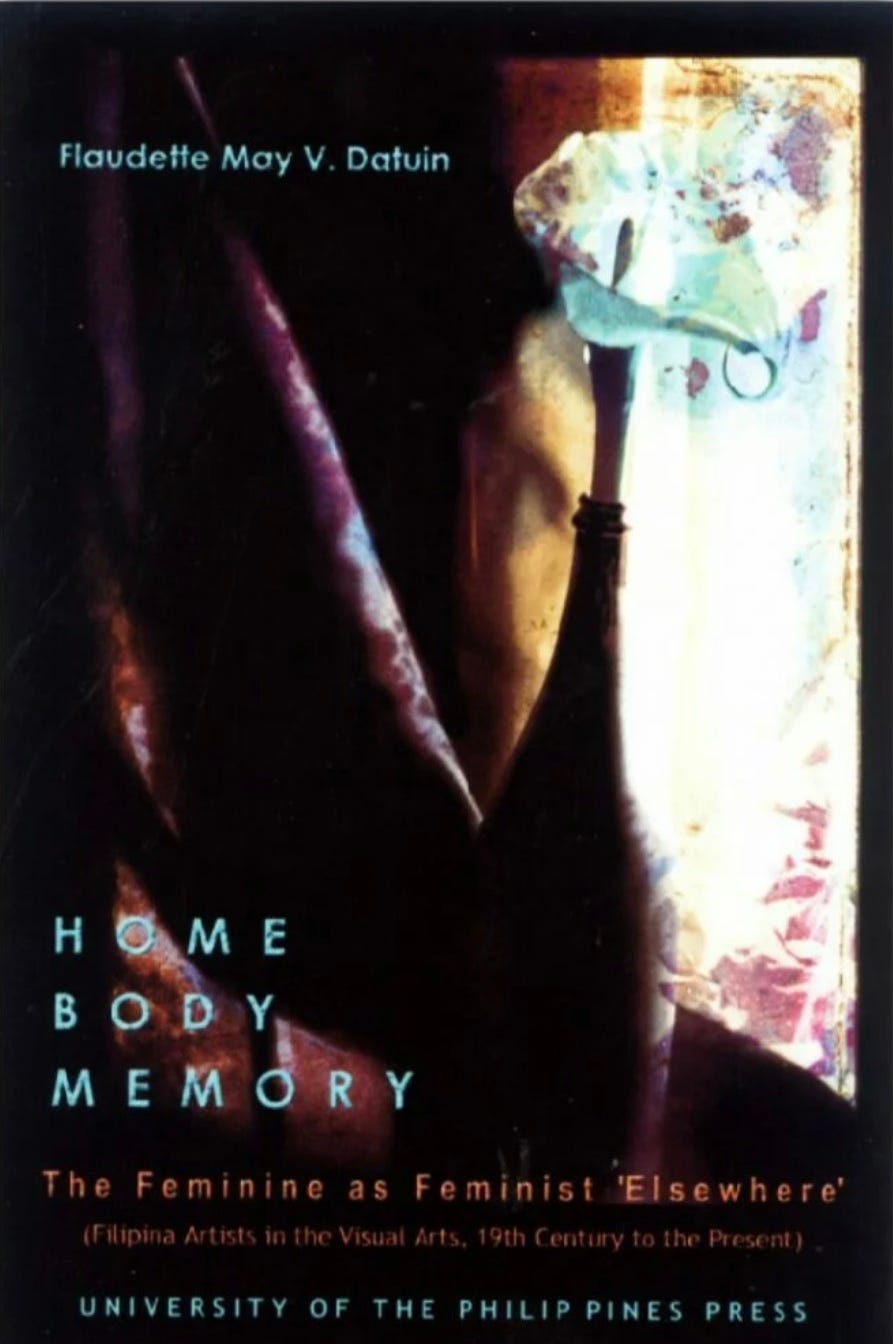

Flaudette May V. Datuin in Home Body Memory: Filipina Artists in the Visual Arts, 19th Century to the Present, the reading Prof. Portia assigned me to report to class, admits finding the nude genre in visual art as “disturbing” because of the fact that “the relationship between the male artist as the master of the gaze and natural world, signified through the naked body of the woman as model and nude, is firmly entrenched in the western academic tradition.” She finds it “twice problematic” when the nude work of art is created by a woman artist for “it lays claim to a territory (the woman’s body) fought over by males.” This claim would cancel out the female artist’s claim over the territory of the nude art which Datuin ceded as historically male. This would be very problematic in view of feminisms that open up all avenues which used to be closed-off to women.

Datuin offered some possibilities for the female nude, that is, by rendering those “imperfect, ugly, and undesirable” bodies visible. The female body, according to Datuin, “is open to a range of possibilities, including its re-appropriation…into a voyeuristic interpretation.” Given this, you as “the woman who looks at [yourself] in the mirror and contemplates [your] naked body…saying that living in and looking at a female body are different from looking at, but not living in it, as a man” is not enough to escape male surveillance.

How devastating that it seems we can never reclaim the female body, our bodies, unless we render them in “imperfect, ugly, and undesirable” states. I am not implying that rendering the female body as such is wrong. It is part of reality, but this is not our only Truth for our Truth also includes our Beauty and our Goodness. How is Datuin’s claim different from how patriarchy is taking our bodies away from us? Why cannot we celebrate healthy female bodies just because we are in the constant anxiety of being under the male gaze?

“To be naked is to be oneself,” John Berger said. “To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself. A naked body has to be seen as an object in order to become a nude.” You are not an object for you are not rendering yourself as one. The look. The touch. The self-recognition. Berger added that “The way the painter has painted her includes her will and her intentions in the very structure of the image, in the very expression of her body and her face.” Your look. Your touch. Your self-recognition. My look. My touch. My self- recognition.

There is an empowering reason behind your name, the The Thinking Nude. We have often been portrayed as passive objects, slaves to our emotions, beings not capable of rationality.

Lluch named you the Thinking Nude because women do think and feel, and live our lives according to reasons and emotions. We reason with things without abandoning our emotions because our emotions are our inner wise Selves telling us what we need, what is good for us, and what we are bound to do for ourselves. This is the aspect that patriarchal society robbed men of. They were taught to only pursue power and reason, and to abandon emotions and so we generally have the kind of men we have today. Men constructed by this culture that gives them primacy and privilege just because they have male bodies.

I go back to when I was a child and thought of the naked body as only a body with no clothes on. The naked female body is inherently neither “good” nor “bad.” I think that women have stopped undressing themselves to look at their bodies in the mirror only because they were made to believe that their bodies constitute a territory that males lay their claims on. They have become detached from whatever having a female body and being a woman had meant for them.

For me, this ekphrastic autotheory mode of writing feminist essay allows me to become like you, a Thinking Nude. Theories and philosophies about my Self that I learned in the ivory tower are concretized by a visual metaphor of an artist. I pose my “I” as, with, or beyond these visual metaphors because of the resonance they have with my lived experiences. My ekphrastic engagement with them is my affirmation that Lluch and I have both struggled over a similar issue. We are sisters by our feminism, where there is no dichotomy between body and mind.

These works of art—whether literary or visual—allow us to achieve self-actualization and to celebrate our Selfhood.

Link to first of three parts

Link to second of three parts

About the author

Amanda Dela Cruz has a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing from De La Salle University, where she also earned her Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy. Since 2021, she has been writing about artists and art exhibitions for Art+ Magazine, as well as taking on coffee table book projects on arts and culture, such as Pamana ng Buhay: A Living Heritage of Biñan and an ongoing one on the legacy of the Benitez family. Her article “Unbuckling the Shackles: A Sex-Positive Feminist Defense of BDSM” was published in the open-access journal Philosophia Vol. 19, no. 2 (May 2018).