For this issue, we have a special treat for our readers! In “Well-Played: A Commentary on Professional Philosophy,” Tracy Llanera (University of Connecticut) writes about “two prominent ways of practicing professional philosophy in the twenty-first century,” for which she uses the analogies of playing chess and staging drama. Her essay inspires response pieces from three colleagues in Women Doing Philosophy. In “Out of Bounds—Thoughts on Tracy Llanera’s ‘Well-Played: A Commentary on Professional Philosophy,’” Jean P. Tan (Ateneo de Manila University) further explores Llanera’s analogies, assessing how they fit philosophizing in the Philippines, particularly her own context. Meanwhile, in “Philosophy as an Ongoing Conversation,” Maria Lovelyn C. Paclibar (Ateneo de Manila University) approaches the topic from her perspective as a philosopher of kwentuhan, or informal storytelling session. Finally, in “So Much Drama! In Praise of ‘Philosophy-as-Theater,’” Noelle Leslie dela Cruz (De La Salle University) elaborates on what philosophy-as-theater may be like, singling out two of her favorite writer-stylists: Stanley Cavell and Jan Zwicky.

Well-Played: A Commentary on Professional Philosophy

By Tracy Llanera

There are two prominent ways of practicing professional philosophy in the twenty-first century. The practice of professional philosophy here refers to the business of writing and publishing journal articles and books for academic purposes. The way I see it, philosophy is either played like a game or staged as a drama.

While these two approaches are not the only ways of doing academic philosophy, they are the most common. Both count for reputation, tenure, and merit in institutions of higher education across the globe. Both are legitimate, and both cut across all kinds of philosophical topics and traditions. The methods, training, and expertise of philosophers prioritize or prize one kind of practice over the other. Some philosophers are skilled at doing both well, but these people are rare. Now let me explain.

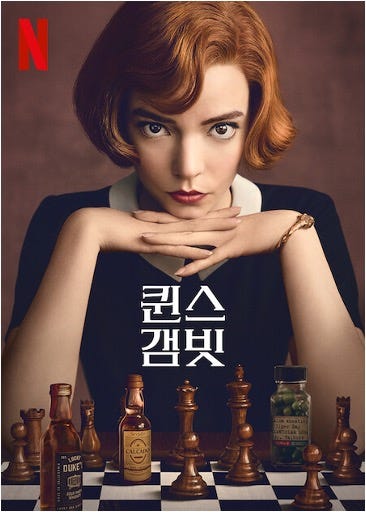

The first way of doing philosophy in the academe is playing it like a game, akin to chess. You have rules and opposing sides. The players are familiar with key concepts and strategic moves, and multiple games are going on simultaneously. There are fancier and more well-funded chessboards than others, and players are hungry to strut their stuff in the most prestigious competitions. There are winners and losers and rematches. To my mind, paradigmatic examples of this approach to philosophy include the countless journal articles in philosophy of language spurred into existence by Robert Brandom’s “Asserting” (1980), the moral philosophy industry of P.F. Strawson’s Freedom and Resentment (1963), the fine-grained debates on conceptual engineering in pragmatism, and the voluminous commentaries generated by Miranda Fricker’s idea of epistemic injustice (some of which, strangely, still boil down to saying something about ideal conditions).

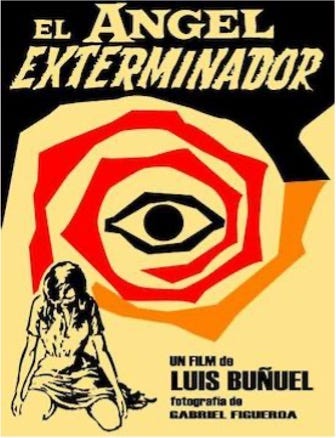

The second approach is staging philosophy as a kind of drama. Central to the plot is a philosophical problem that all of us could muddle through together. In this set up, the philosopher plays all the roles: the director, actor, storyteller, props manager, even theater critic. The point is less about one-upping another production, but about revealing or illuminating something about the world or about people in its own, unique way. Some theaters are fancier and more well-funded, and some scripts are more dry or convoluted or bizarre than others. Classic examples of this kind of philosophy, in my opinion, are Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks (French: Peau Noire, Masques Blancs, 1952) Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (French: Le Deuxième Sexe, 1949) and Richard Rorty’s Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (1989). Digesting the philosophical import of these books could feel, among others, like you’re waiting for Godot á la Samuel Beckett, or grieving with the righteous rage of the oppressed like Bertolt Brecht, or witnessing the upper-class caste reveal their filth and animality, as Luis Buñuel has brilliantly shown us in his cinematic repertoire. Readers are likely to find things unresolved at the end of reading these books, with some souls buzzing with even more difficult existential questions compared to when they started. But, when the drama of philosophy is staged with wisdom and bravado, its patrons emerge richer, a little wiser, and more connected to the lives of others afterwards.

Here's my hot take. What makes professional research in philosophy dissatisfying is that these two distinct approaches are converging irresponsibly in more and more research projects. Often, the authors are not aware of what is happening or who their conversation partners are in their writings, and the result is misguided, bad, or null philosophy. For example, when chess-playing philosophers arbitrarily decide to perform a tragedy, they sometimes end up staging a boring and fruitless game for the audience; and, when philosophers of theater cast only black and white pawns, bishops, and queens as major characters, they miss appreciating the perspective that a whole rainbow of actors on stage might be required to make their projects fly.

I am not saying that these two approaches cannot overlap to explain a philosophical idea, or that philosophers of a particular stripe are better off sticking to one way of philosophizing for the rest of their lives. Again, there are philosophers who use both strategies in their writings and produce truly compelling work; in my department at the University of Connecticut, for example, there’s Michael Lynch and Lewis Gordon who are both setting the example of how this can be done. The problem is that sometimes, philosophers are uncritical or even wholly ignorant of the design their projects require or the purpose they serve.

The metaphilosophical point is this: our conscientiousness about our philosophical approach matters. We should think about what we are doing and who we are writing to when we write philosophy. We must also be able to ascertain when the tools and techniques we are employing in our research projects are not the best ones for the job. And, if push comes to shove, we must learn how to change gears and execute the task in a different day.

* * * *

Author’s note

I gave this talk at the World Philosophy Day Event: Metaphilosophy Workshop (November 2024) at the University of Connecticut. I thank the Philosophy Graduate Student Association (PGSA) and the UConn Department of Philosophy for organizing this event.

About the Author

Tracy Llanera is Associate Professor of Philosophy at the University of Connecticut, USA. She is author of Richard Rorty: Outgrowing Modern Nihilism (2020), co-author of A Defence of Nihilism (2021), and editor of Resilience and the Brown Babe’s Burden: Writings by Filipina Philosophers (2024). Llanera works at the intersection of social and political philosophy, philosophy of religion, feminist philosophy, and pragmatism, specializing on the topics of nihilism, extremism, conversion, and the politics of language. She is a core member of Women Doing Philosophy, a global feminist organization of Filipina philosophers. Her website is https://tracyllanera.com/.

Out of Bounds—Thoughts on Tracy Llanera’s “Well-Played: A Commentary on Professional Philosophy”

By Jean P. Tan

In her brief metaphilosophical commentary delivered at the University of Connecticut during a World Philosophy Day event in 2024, Dr. Llanera criticizes a growing trend she has observed among philosophy practitioners of injudiciously mixing distinct paradigms of philosophic writing, namely, playing philosophy like a game (particularly, chess) and staging it like theater. Without knowing the specific targets of her polemic, it’s difficult to assess how compelling her diagnosis is of the philosophical status quo. I can see how a philosopher of theater could falter by casting competing positions in overly simplistic black-and-white terms. But I’m not sure I understand what it would mean for chess-playing philosophers to attempt—and fail—to stage a tragedy.

What does it mean to dramatize a chess match? Or to turn theater into chess? In the case of the former, would it be a matter of infusing pathos to a game dominated by rules? Or conversely, in the case of the latter, of taming the dramatic pathos of existential reflection with the regimented structure of argumentative logic? Is it an issue of the use of rhetorical strategies, or is the point of the juxtaposition rather the manner of engaging in polemics?

It appears that the main contrast being drawn by Dr. Llanera is that philosophy played as chess is concerned with winning an argument, whereas philosophy played as drama is less concerned with “one-upping another philosophy production” than with “illuminating something about the world.” Since, I take it, the author is suggesting neither that chess-playing philosophers are not as concerned with “illuminating something about the world,” nor that the philosophers of theater are unconcerned with contending with competing positions, perhaps the point of the juxtaposition could be stated as follows:

The main difference I see between the chess-player and the playwright is that the chess-player, while being literally outside of the chessboard, is actually within the game. Ultimately, the king is the chess-player’s surrogate on the board, whereas the playwright is outside of the play no matter how closely they are identified with one of the play’s characters. The play, as Aristotle would say, is a mimesis of action. But to play a game is not to imitate action; playing chess, one is not representing a battle but is engaged in one, with the result that one either captures or is captured by the other king.

On my reading of the analogy, the fundamental difference between the two modes of doing philosophy would be that the chess-playing philosopher is directly engaging other philosophers polemically in one’s writings. Each article (this genre of philosophy, I take it, is primarily played on the board of journal publishing) constitutes the philosopher’s move, which invites one’s opponents to make their own moves. On the other hand, the philosopher as dramatist presumably engages in polemics at some remove from direct confrontation with one’s opponents, staging conflicts within the confines of the text (which, I take it, must for the most part be in the form of the full-length book.)

Books, of course, can be just as polemical as journal articles—as Dr. Llanera’s examples of “theater philosophy” attest—and articles, as much as books, do stage conflicting positions within the confines of their short form, so I’m not sure how far the analogy as I have constructed it holds, or how heuristically useful it is for conceptualizing contrasting philosophical approaches.

On this interpretation, Dr. Llanera’s call for clarity about one’s aims and methods could be understood as the requirement to think about how polemics is being played out in one’s writing—whether one is primarily engaged with an external opponent or with the self. But since these are not mutually exclusive intentionalities—and I daresay, good philosophizing is always a matter of thought struggling with itself—it doesn’t seem wise to insist on a hard and fast distinction between these two modes of doing philosophy.

But perhaps, the issue of polemical structure is not the point of Dr. Llanera’s distinction. In any case, regarding her call “to ascertain when the tools and techniques we are employing in our research projects are not the best ones for the job,” in order to determine whether one’s way of proceeding is appropriate for one’s purpose, it first has to be said what sorts of purposes are better served by the chess-playing mode of philosophy and which are better approached through the theater mode. Without such criteria, it’s not clear how one could make a strategic choice between the two modes, or how one should go about judiciously fusing the two approaches in one’s writing.

I suspect that as things stand, the choice of approach is not so much a matter of determining the means appropriate to one’s ends but is rather determined by the choice (or merely accidents?) of one’s interlocutors. In other words, the “type” of philosophical writing one employs is probably more a function of which philosophers you are “hanging out with,” which readership you are addressing, whose arena of philosophy you are entering, which rhetorical rules govern such spaces, which philosophical conversations you have been admitted to, than it is a matter of choice of writerly strategy. If your interlocutors are playing chess, wouldn’t your piece be a move in response to theirs?

If, indeed, more and more philosophical writings combine previously distinct approaches, it might be the case that boundaries are shifting, and new rules are emerging among the existing philosophical language games. The significance of this possibility might be worth examining.

Dr. Llanera’s call for clarity and self-awareness about one’s writing projects is certainly worth heeding, but not only for the sake of effectively making one’s philosophical point. More importantly, we should be mindful of the extra-philosophical limits imposed upon us by the historical and socio-political givens governing the language games of professional philosophy.

From Dr. Llanera’s context, she finds “these two distinct approaches converging irresponsibly” to be a source of dissatisfaction with professional philosophy. But from where I am standing, namely, in the Philippines, what gives me grief is something entirely different. For me, the main source of dissatisfaction is that academic philosophy in the Philippines interpellates me as an outsider, a spectator (whether it be of a chess match or a play), at best a commentator of philosophical canons from the West, or as a thinker who merely extends and applies concepts to my particular context or continues a conversation that was initiated (and continues to be funded) from the global north.

The conscientiousness that my situation calls for is of a different order. Conscientiousness demands that I ask whom I am addressing as a philosopher? It consists in deliberately training my efforts and attention to my own historic-cultural context—in all its complexity and contradictions—and participating in the creation of collective scholarly practices from which I and other scholars like me can create concepts, raise and address our own questions, speak in our own voices.

Philosophy as an Ongoing Conversation

By Maria Lovelyn C. Paclibar

Dr. Llanera's essay offers an interesting commentary on professional philosophy in the 21st century. It took me a while to find my position before I could offer a response. Perhaps this is because I had to grapple with two experiences of displacement effected by the essay.

First, I was displaced by the idea of professional philosophy. Second, by the invitation to be extra aware of one’s approach in philosophizing.

Though this is not the first time I would hear the term professional philosophy, and even if Dr. Llanera has clarified this to mean “academic philosophy,” the term still feels foreign to me. Perhaps I have been accustomed to the use of “professional” in everyday language as referring to doctors or lawyers. In that context, one can easily understand “professional” to mean an expert in something. But what is a professional philosopher an expert in?

It was actually through Richard Rorty in Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature that I first came across the term “professional philosophy,” and Rorty was not exactly speaking of it in favorable terms. He stated,

To drop the notion of the philosopher as knowing something about knowing which nobody else knows so well would be to drop the notion that his voice always has an overriding claim on the attention of the participants in the conversation. It would also be to drop the notion that something called “philosophical method” or “philosophical technique” or “the philosophical point of view” which enables the professional philosopher, ex officio, to have interesting views about, say, the respectability of psychoanalysis, the legitimacy of certain dubious laws, the resolution of moral dilemmas, the soundness of schools of historiography or literary criticism and the like.

It is in this work where Rorty unseats philosophy as the “queen of all sciences,” or as “the judge of truth.” By holding the presumed role of the professional philosopher in question, Rorty, who was clearly aware of what he was doing, was ushering in the demise of philosophy and its foundational status. In the end, Rorty redeemed philosophy and the philosopher by arguing for a more pragmatic role—that of the facilitator of edifying discourses, which he describes as endless conversations on fundamental disagreements, that are fruitful nonetheless, because of how the conversations can open up the perspective and imagination of participants.

Rorty’s idea of an edifying discourse captures both methodological positions described by Dr. Llanera in her essay. First, philosophy being a game of chess regulated by rules and constituting opposing sides echoes the idea of philosophy as discourse. The intelligibility of discourses rests on following a set of implicit rules, such as in Jürgen Habermas’s unavoidable presuppositions about the rules of communication or Ludwig Wittgenstein’s idea of language games. Moreover, the to and fro movements of the game of chess faithfully capture the dialectical structure of conversations, which end with victory to one side, but can be opened anew. Second, at the same time, the edifying aspect of philosophical discourse follows the revealing or illuminating quality of philosophy as a drama. The conversations hardly reach agreement or consensus, which, for Rorty, is how philosophy should be, given that it has lost its foundational status or privileged access to truth. The disagreements can still be fruitful insofar as they are edifying, a point which resonates with Dr. Llanera’s description of philosophy as a drama:

Readers are likely to find things unresolved at the end of reading these books, with some souls buzzing with even more difficult questions compared to when they started. But, when the drama of philosophy is staged with wisdom and bravado, its patrons emerge richer, a little wiser, and more connected to the lives of others afterwards.

From this perspective, philosophy as an edifying discourse is both a game and a drama. This brings me to ask the question about what Dr. Llanera means by the two approaches “converging irresponsibly.” Is the convergence of the two approaches up to the responsible decision of the professional philosopher or is it something that is already happening the moment one steps into philosophy? If it is the latter, does the philosopher have the power to design the convergence? And if they do consciously man the convergence of the two approaches, will this not curtail both the to and fro movement of the game and the edifying character of the drama?

This brings me to my second displacement, which has to do with the invitation to be extra-aware of the method or approach one uses in professional philosophy. Wouldn’t such hyperawareness impede the flow of the conversation when we pay too much attention to our method?

To be clear, I recognize the importance of being aware of our methods in philosophy. In fact, I would advocate for it even more given the blatant lack of this awareness among the professionals from my side of the world.

This reminds me of this one time I was asked to elaborate on my methodology in a paper abstract I was going to submit for a conference. Trying to identify the methodology of a research that I have already conducted and written about was both funny and illuminating for me. It was a clear reminder that many of us in philosophy do not really follow the way other disciplines do research, which is to specify in our introduction what methodology we used to gather, analyze, and draw conclusions about data. I believe that this silence on methodology is still a continuation of the belief that philosophy remains above the sciences. This view speaks much about the arrogance of professionals in this field.

While Rorty criticized this arrogant position, he also criticized those who treat philosophy as a form of scientific discipline (something which started with Descartes and Kant and a slew of modern epistemologists – an unfortunate turn in the history of philosophy according to him). I do not agree, however, with Rorty’s dismissal of the disciplinal turn of philosophy. Like Dr. Llanera, I recognize the importance of being conscientious about our approach and methodology. To be aware of how the mind is trained to look, to categorize or conceptualize, and to make certain conclusions, allows for the possibility of repetition and habitual development. The philosopher’s well-trained eyes see more than the ordinary eye because of this habituated way of arranging messy-rich reality in a particularly coherent way. This is not so different from the way an eye trained for art sees nuances in a work, or an eye trained for climate change sees subtle changes in the atmosphere.

I agree with Dr. Llanera that we need to be more conscientious about our approaches when philosophizing. But my reasons for advocating this stems less from a concern for making the exercise a satisfying one, that is, whether the game or the drama excites and enthralls the audience. Although that can always be a welcome bonus for everyone involved, I think putting premium on this goal would subdue the very source of excitement of the exercise, which in my view, is the moment of being decentered by an edifying question. If the professional philosopher has to be conscientious about his or her method, it should be because they are concerned about making sure that the question reaches their audience and invites them to make the question their own, thereby encouraging them to join the conversation. In the final analysis, if philosophy must be regarded as a profession, if we are to ask what a philosopher should be an expert of, then it has to be that of a commitment to let the conversations flow.

So Much Drama!—In Praise of “Philosophy-as-Theater”

By Noelle Leslie dela Cruz

Dr. Tracy Llanera’s essay on what she perceives to be the two main styles of contemporary philosophizing had me thinking about my own preoccupations in the interstices of philosophy and literature. This is especially relevant because I am teaching a course on the philosophy of literature this term, and one module focuses on “philosophy as literature.” (The preposition “as” indicates that the focus is on an oft-neglected aspect of philosophy, which is the literary style in which it is inevitably written.)

Philosophy has always taken on a bewildering array of forms—“philosophical genres”—over the centuries, from the Platonic dialogue to the Cartesian meditation to the Nietzschean aphorism to the Wittgensteinian tractatus to the Beauvoirian memoir. However, in the present day there is a palpable poverty of style as reflected by the predominance of the professional philosophy paper (PPP). Done well, it’s a remarkably efficient form of written reasoning that allows for communal discussion in the pages of respected peer-reviewed journals. However, the discussion may be indefinitely extended, more often than not ultimately zeroing in on a set of conceded technicalities that may appear to be only so much trivia to non-philosophers. This development is a product of institutional practices, and consequently something that is difficult to avoid for academics.

It is this context we should have in mind in pondering today’s two broad approaches to philosophizing. Dr. Llanera uses chess and theater as analogies. Philosophy-as-chess gestures at a self-contained game with clear objectives. She cites the writings of Robert Brandom, P.F. Strawson, and Miranda Fricker as examples. Philosophy-as-theater, on the other hand, is a full-bodied production that is about no less than the whole world and human life. She cites as examples books by Frantz Fanon, Simone de Beauvoir, and Richard Rorty. What’s problematic for Dr. Llanera are confused attempts to merge the two:

What makes professional philosophy dissatisfying, in my view, is that I’m seeing these two distinct approaches converging irresponsibly in more and more research projects. Often, the authors are not aware of what is happening in their writings, and the result is misguided, bad, or null philosophy.

I should like to hazard a possible explanation for this trend, at least from the perspective of philosophers who have a grand idea but who are forced to express it in terms of a rigorous, easily-gamed/gamified system. There is a relative value assigned to each of the two approaches. The entrenched status of the PPP as paradigmatic philosophy incentivizes people to play chess and disincentivizes them from writing plays. Anglophone philosophers in the global north, where scholarly training tends toward the chess-playing variety, excel at the game of accumulating high h-indices. The philosophy paper published in a Scopus-indexed journal with a Q1 SJR ranking is institutionally rewarded. The more hybrid type of work, say an interdisciplinary attempt to think the political philosophy of a poet, languishes in desk rejection limbo. The irony is that it is harder to produce the latter. I think this is because its thought rebels against the confines of the PPP. If not done well, philosophy-as-theater may be held up to ridicule as a prime example of intellectual laxity or even derangement. By comparison, philosophy-as-(incompetent)-chess is merely dismissed.

In my own reading and research, two contemporary philosophers stand out as exemplars of Dr. Llanera’s philosophy-as-theater. They don’t necessarily balance the two putatively competing impulses of conceptual clarity and dramatic expression, as her admired writers do (she mentions her eminent colleagues at the University of Connecticut, Michael Lynch and Lewis Gordon, as writers who effectively combine the two approaches). Rather, the works of the philosophers I have in mind exploit the affordances of linguistic and stylistic expression to a much greater degree than the PPP ever can (or PPP’s expanded version, the philosophical treatise). For the ambition of their projects, no less than invented forms will do.

One of these philosophers is the late Stanley Cavell. I first came across his work when I read The Senses of Walden, his reading of Henry David Thoreau’s famous paean to Walden Pond and simple living. At that time, I had no idea about the significance of Thoreau or American Transcendentalism, but such was Cavell’s take on Thoreau’s use of language that I just had to pore over Walden. Inevitably, it became one of my all-time favorite books, and I even went on a pilgrimage to the author’s reconstructed cottage, erected on the site where the original one had been. (Amor Towles is similarly a fan, as I found after I read his novel The Rules of Civility.) Now, I always include Cavell’s work as part of my course readings for philosophy of literature. Of note is his analysis of Shakespearean plays, in which he would, for example, demonstrate the loneliness of the Cartesian subject, its impossible epistemic project, through what reads like a psychoanalysis of Othello! Commentators are bewildered about what he’s trying to do; certainly his reading of Shakespeare is not literary criticism, but neither is it something that philosophers could easily categorize. Is he doing epistemology, or perhaps a meta-epistemology? Can a philosophical reading of a piece of literature even serve as an argument? What if it flies in the face of standard readings of a text, precisely because a faithful reading is not the point?

The other writer I admire as a philosophical dramatist, so to speak, is Jan Zwicky. A poet and violinist, she has written—among other things—two big works in the style of the commonplace book, Lyric Philosophy (1992) and its follow-up, Wisdom and Metaphor (2003). Schooled in the Anglo-American analytic tradition, she studied Wittgenstein and came to fuse his ideas with those of Freud and the Gestalt psychologist Max Wertheimer, to philosophize about language and meaning. Lyric Philosophy and Wisdom and Metaphor resemble scrapbooks containing various materials: snippets of text, poetry, quoted passages, photographs, illustrations, etc., deliberately placed side-by-side in each spread so as to bring out the resonances between the two texts so displayed. So unusual is her style that a special issue of the journal Common Knowledge (Volume 20, issue no. 1, Winter 2014) featured two essays by Zwicky and responses from various philosophers, among them John Koethe (who, like Zwicky, is also known as a poet).

Unfortunately, the ideas of these thinkers are only infrequently discussed in the mainstream philosophy journals. In Cavell and Zwicky, there’s no ongoing chess tournament whose progress you could spectate, to extend Dr. Llanera’s analogy. If they’re talked about at all, their works become the subject of analysis written in the PPP style, as though these were curiosities that dramatize or embody, rather than actually say something about, meaning (a traditional preoccupation of philosophy). And while I love reading and engaging with philosophy-as-theater, I continue to be confined by institutional practices and conventions that require me to write PPPs—at least insofar as I wish to keep earning a living—and to teach my students to write PPPs.

Is it too late to change philosophy? Are the prevailing norms too embedded in the (academic) way of life for the contemporary age to produce another Wittgenstein or Beauvoir? After all, running a theater requires more than a single playwright: It needs an entire cast of characters, props, facilities, stagehands, and perhaps most of all, an audience. Doing philosophy differently is not just a matter of studying alternative ways of writing and emulating them—or even offering the occasional fringe course that explores philosophical genres. It requires the organic development of communities that have an entirely different set of questions, concerns, and priorities. These communities may have to be, as Beyond the Ghetto founder Dr. Jean Tan likes to describe the projects of BTG, “para-institutional,” permeating the academe and drawing resources from it, but not ultimately bound by it. Only then can we recognize a more meaningful type of philosophy when it is being performed. Then, we must support its production and value the output. But perhaps most importantly, we ourselves must actively participate in the drama, becoming avid theater-goers, critics, and producers.