On Socrates and Tasyo, from Plato through Kofman to Rizal: Reflections on Figures of the Philosopher

Issue no. 37 (First of two parts)

By Jean P. Tan

This is a revised version of a lecture I delivered last November 2023, upon the invitation of the Senior AB Philosophy Students of the University of Santo Tomas. The seminar was entitled “Footnotes: The Legacy of Ancient Greek Philosophy.” The thoughts I am sharing with you here are more exploratory and suggestive than fully worked out. Where I speak of Sarah Kofman’s ideas, it is more in the manner of an invitation to discover her works, rather than a systematic introduction. And the musings I offer are meant to open lines of inquiry for your consideration, rather than present satisfactorily argued intuitions.

1. Socrates and Plato

The title of the seminar that occasioned these musings, “Footnotes,” calls to mind the famous remark of Alfred North Whitehead locating Plato as an origin of inspiration of European philosophy. And with the mention of Plato comes — to use a term frequently used by Sarah Kofman — his double, Socrates.

Philosophy can write footnotes to Plato’s writings, but what does it make of Socrates? Between Socrates—who left no writings, but whom Plato presents in his dialogues as speaking, walking, drinking, and even dying—and Plato, who wrote aplenty, but whose presence recedes behind the dramatic philosophical encounters depicted in these dialogues— between Socrates and Plato is a hiatus which persists in academic philosophy as we know it today.

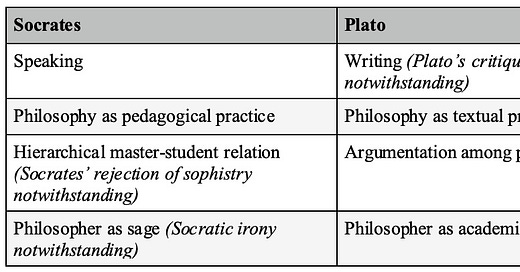

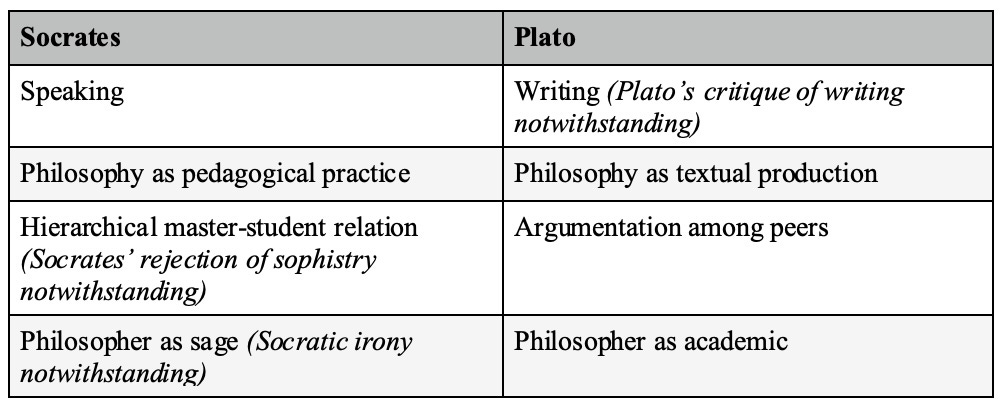

We normally take for granted the gap or tension between these differing aspects or conceptions of philosophic practice: namely, philosophy as a practice of writing, of textual production, of argumentation among peers, on one hand, and philosophy as pedagogical practice, inherently hierarchical, on the other; between two conceptions of the philosopher: the philosopher as academic and the philosopher as sage; and between two conceptions of philosophy: namely, philosophy as a field for experts and philosophy as a way of life.

These contrasts are, of course, oversimplifications. The opposing conceptions are more intermingling tendencies than discrete types. And the pairs of dichotomous terms do not neatly line up with one another (as my qualifications in parentheses show). Nevertheless, this schema might serve some heuristic purpose. It could serve as a starting point for reflecting about our Greek inheritance not only at the level of ideas and worldview, but at the level of forms of practice.

What is our self-conception as philosophers? In our classrooms, conference rooms, and writings, with whom do we speak, and how? To whom and for whom do we write? And whom do we exclude?

2. Sarah Kofman’s Socrates

Sarah Kofman (1934-1994) is a French philosopher best known for her works on Nietzsche and Freud and for her autobiographical works that belong to Holocaust literature. Her major book on Socrates is called Socrates: Fictions of a Philosopher.

In this work, Kofman reads Hegel, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche and offers comparative reconstructions of how each of these philosophers renders his own version of Socrates in a manner that fits his own philosophical system or project. (Kofman reads Hegel, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche as writing “novels” about Socrates, in other words.)

Before launching into her reconstruction of these three fictions of Socrates, Kofman begins with another Socratic fiction — her own reading of Plato’s Socrates as depicted in the Symposium. In this fourth novel, it could be argued that Kofman is enacting a Platonic gesture — the dramatist receding behind the stage — of presenting the Socrates in the Symposium as Plato’s rendition of Socrates. Just as Plato stood behind Socrates, receding behind Socrates in the very act of appropriating Socrates, so Kofman stands behinds Plato in her reading of the Symposium.

Kofman’s reading of Socrates of the Symposium begins with a Jewish American joke that she borrows from Freud:

Two self-made men have had their portraits painted. Very proud of the likenesses, they put the paintings on display side by side, at an evening party, along with other marvels. Instead of admiring the portraits, however, one art critic exclaims: ‘But where’s the Saviour?’1

The joke is twofold: in one stroke, by implying that the two wealthy men are thieves, it undoes all their pretensions to worldly esteem, and at the same time — and this is the move that brings the joke to a keener fusion of the comic and the tragic — shows the place of the Savior as an empty space. The art critic’s question, “Where is the savior?”2 teeters precariously at the point of passing over to the question, “Is there a savior?”

In the Symposium, according to Kofman, the portrait of Socrates is framed between two other portraits:

Two portraits of Socrates frame the Symposium, one painted by Aristodemus, the good thief, the best of the deme, the other by Alcibiades, the bad thief. Between the two, the figure of Diotima-Socrates-Plato hangs a third mythical portrait, that of the demon Eros, son of Poverty (Penia) and Resource (Poros), an atopic figure of the intermediary.

On this reading, the dialogue is bookended by two doubles of Socrates, two followers and lovers of Socrates who seek to emulate him, neither of whom succeeding in grasping the elusive Socrates: Aristodemus, who came as Socrates’ companion — the uninvited guest who had to suffer the embarrassment of arriving at Agathon’s ahead of Socrates (as the latter stood lost in thought in some neighbor’s porch) and the famous Alcibiades — the gatecrasher who heaped upon Socrates his lavish double-edged encomium for being a master seducer.

Kofman’s Socrates is presented as an atopic figure. Someone who cannot be placed, or put in his place, ambiguous and contradictory. Is Socrates godlike or monstrous? Is the philosopher lost in thought inspired or catatonic? Alcibiades cannot decide whether Socrates’ imperviousness to his seduction makes him superhuman or if he, Alcibiades, should admit that he has fallen prey to Socrates’ manipulations.

An enigma, Socrates keeps slipping through our fingers. At the beginning of the Symposium, Socrates could not be found — Agathon asks about his absence when Aristodemus, Socrates’ shadow, arrives at the party alone. And at the end of the dialogue, after outdrinking and outlasting Agathon (the tragic poet) and Aristophanes (the comic writer) in conversation, Socrates gets up — without having slept — goes to bathe, goes about another full day before finally going home to sleep.

What makes Socrates such an enigmatic figure? What is it that makes Socrates an object of fascination for philosophers who fashioned their own fictions of the philosopher? On my understanding of Kofman’s Socrates, we can perhaps put Kofman’s answer in two ways — which as we shall see, come down to the same thing.

(1) Socrates casts a long shadow of fascination because we are confronted with the question of the meaning of his death. What do we make of the death of Socrates? For us, inheritors of the Socratic legacy, what is at stake is the meaning of death for the philosopher: Thus, the question is, What do we make of Socrates’ attitude towards death?

This leads us to the second point regarding the enigma of Socrates: (2) Irony in the face of death — this is the question regarding Socratic irony. At the heart of the enigma of Socratic irony is the question: What are we to make of Socrates’ last words?

At the close of Phaedo, at the telling of Socrates’ death, Plato writes:

… when he uncovered his face, for he had covered himself up, and said—they were his last words—he said: Crito, I owe a cock to Asclepius; will you remember to pay the debt? The debt shall be paid, said Crito; is there anything else? There was no answer to this question…3

Are Socrates’ last words an expression of a sublime wisdom in the face of death or is it, as Nietzsche says in The Gay Science, a “ridiculous and terrible ‘last word’” that he should have refrained from saying?

‘O Crito, I owe Asclepius a rooster.” This ridiculous and terrible ‘last word’ means for those who have ears: ‘O Crito, life is a disease.’ Is it possible that a man like him, who had lived cheerfully and like a soldier in the sight of everyone, should have been a pessimist?4

Kofman offers no answer to the enigma of Socrates but only a conjecture about how being unsettled by Socrates’ atopia has generated various attempts by philosophers to regain their self-mastery. At the conclusion of Socrates: Fictions of a Philosopher, Kofman suggests that perhaps Hegel, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche were fascinated by Socrates because they had accounts to settle with Socrates. They had to confront the enigma of Socrates and in various ways come to terms with the destabilizing figure of Socrates so that they might save their philosophical systems and certitudes from collapsing.5

Sarah Kofman, Socrates: Fictions of a Philosopher, translated by Catherine Porter (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998), 11, citing Sigmund Freud, Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious.

“…Socrates-as-Savior is yet another fiction.” (Kofman, 13.)

Kofman, 13-14.

Plato, Phaedo 118.

In her readings of the three constructions of Socrates, Kofman highlights the attitudes of Hegel, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche towards femininity and the maternal. She concludes that in constructing their accounts of Socrates, all three of these philosophers were contending with their own femininity.

Thanks for sharing