By Noelle Leslie dela Cruz

Contents

Introduction

A Filipino nanny program: Filipina caregivers in Seoul

Care and women’s bodies: Works by Filipina artists at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

A safe space for women: Ewha Womans University

Postcript: Caring men

Introduction

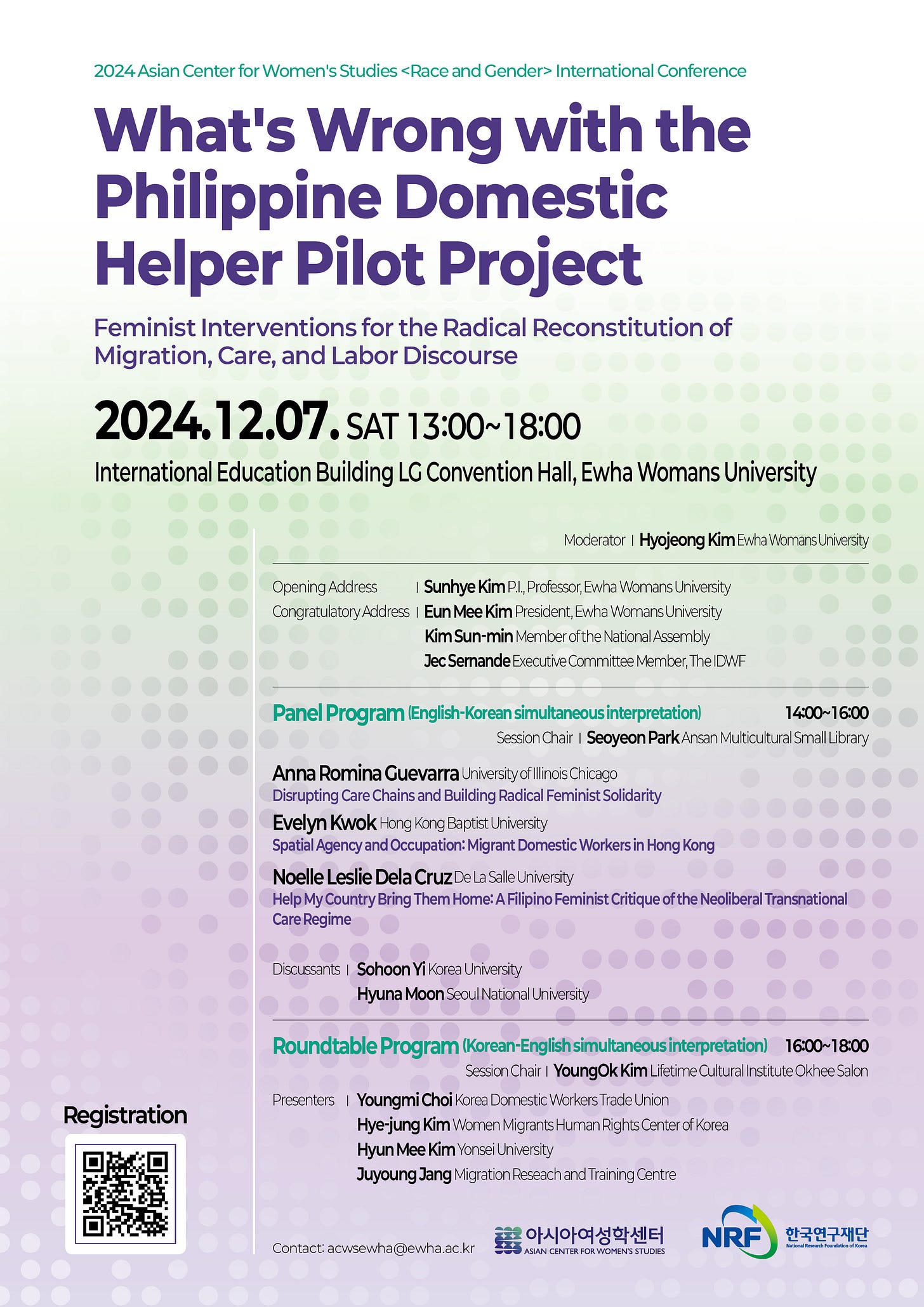

Over the past five days, I’ve been able to combine work and pleasure during a trip to the Republic of Korea, as I participated in a conference critical of the Seoul city government’s Philippine Domestic Helper Pilot Project. Under the auspices of the Asian Center for Women’s Studies (ACWS) at Ewha Womans University, the conference featured me as one of the main speakers, since Filipino migrant care work was a key theme and I’ve previously published on that. The irony was not lost on me that I was only able to do this—i.e., engage in discussions about the meaning and value of care work—because of the “invisibilized” care work that other people routinely perform for me. For that, I am grateful, as well as for the warm reception I received among the faculty, students, and researchers at the ACWS. Special thanks to Dr. Sunhye Kim, who heads ACWS’s Race and Gender Project; ACWS research fellows Hyeojong Kim and Minji Yoo; and my fellow speakers Dr. Anna Romina Guevarra (University of Illinois) and Dr. Evelyn Kwok (Hong Kong Baptist University).

It was my first time in Korea, and I was wildly impressed by this country, as well as by Ewha. I’ve been posting about my trip in social media, but not about the conference itself, since there is so much to say about the latter and I wanted to present my thoughts in an organized way. Coincidentally, when I first arrived last December 6, the country was in political turmoil as President Yoon Suk Yeol declared, and then later rescinded, martial law. Although there were plenty of attendees at our event, there would have been more if people had not been busy protesting at the National Assembly Building. As of this writing, the President has survived the impeachment process, largely through the machinations of his political party mates, but he is under ongoing investigation for rebellion. Regime change appears to be the theme of the month, and should there be one in the Republic of Korea, it would have significant ramifications for the issues we’ve talked about during the conference.

A Filipino nanny program: Filipina caregivers in Seoul

The conference itself was entitled “What’s Wrong with the Philippine Domestic Helper Pilot Project? Feminist Interventions for the Radical Reconstitution of Migration, Care, and Labor Discourse.” For the first time, Korea is instituting a Filipino nanny program, comparable to those in Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, the primary Asian markets for Filipino temporary migrant domestic workers. The program, the brainchild of Seoul city mayor Oh Se-hoon, and which has the support of President Yoon, commenced in September, when 100 pre-selected Filipino care workers started working for select Korean households. The pilot will run for six months, terminating in February 2025. In spite of public criticisms—The Diplomat reports that these have to do with the qualifications of the workers, the scope of their work, the impact of cultural differences, and whether or not they should receive the Korean minimum wage—the city is already gearing up for its widespread implementation.

The rationale given for this initiative is the need to reverse the rapid decline of Korea’s total fertility rate (TFR). This represents the number of children a woman is expected to have during her reproductive years. A TFR of at least 2.1 is required in order for the population of a developed country to exactly replace itself from one generation to the next. Korea holds the world record for the lowest TFR at below 0.7. If this demographic trend continues, the aging population will not be replenished, and it could spell the end of Korean society and culture in just several generations.

Enter the Filipino nanny. If she could help alleviate the care burden in Korean society, perhaps more Koreans (i.e. Korean women, who currently bear the brunt of the burden) would be incentivized to get married and have children. In this way, the program appears to constitute a win-win situation for both labor-receiving and labor-sending countries, as it alleviates the care crisis in Korea while providing another income stream for labor migrants from the Philippines.

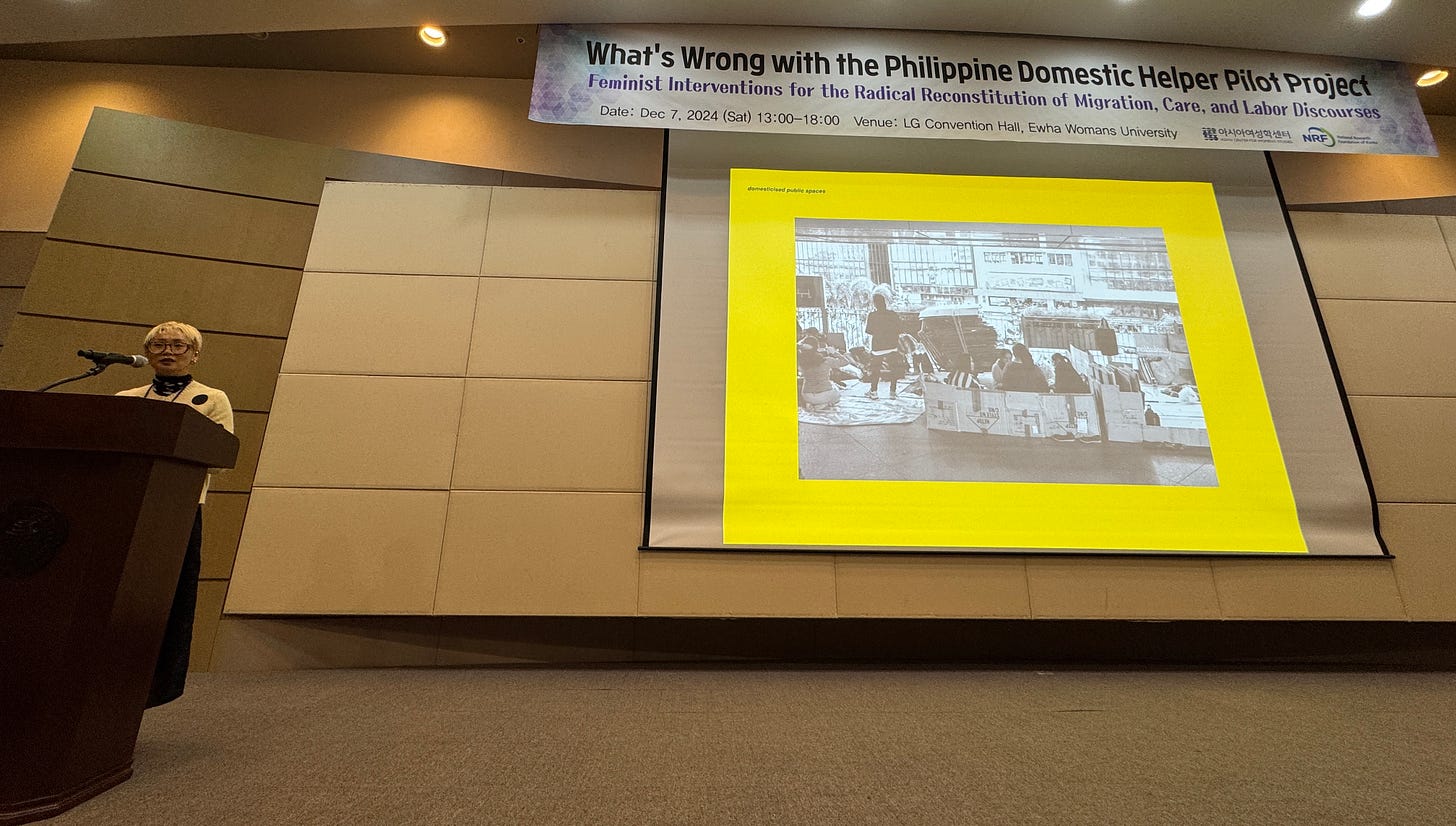

During the conference, we challenged this idea, discussing such topics as the construction of gender across cultures; the devaluation and feminization of care work (or, to use the broader Marxist feminist term, social reproduction); Korea’s rigid patriarchal culture; the paradoxically high gender gap index of the Philippines, notwithstanding that it is far behind Korea economically; the Philippines as a “labor brokerage state,” to use Robyn Magalit Rodriguez’s phrase; and the victimization of, as well as the agency exercised by, Filipina migrant domestic workers. Dr. Guevarra presented her vision of feminist solidarity among Korean and Filipino women in building an alternative care regime. Dr. Kwok talked about the ways that Filipino domestic workers in Hong Kong occupy space in the context of their cramped lived-in working conditions. Finally, I presented my critique of what I call the neoliberal transnational care regime, which reveals the limitations of existing care-based political theories such as Joan Tronto’s. The complete conference proceedings, in both English and Korean, are available online.

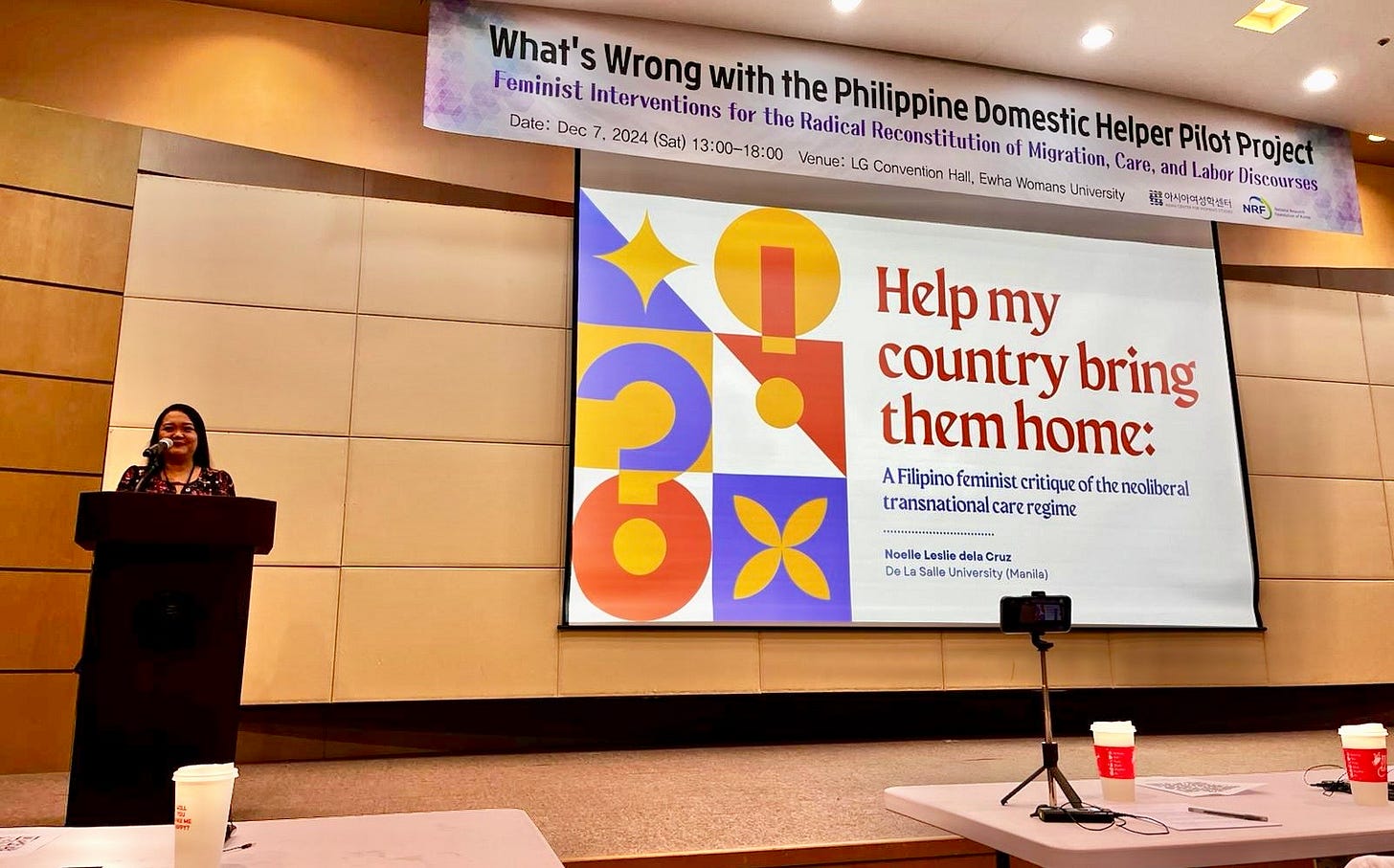

We were all in principle against the Philippine Domestic Helper Pilot Project, and critical of the (neoliberal, capitalist, sexist) structures that have brought it about. Our positions are very nuanced and our proposed solutions a mix of short- and long-term actions. I’ll just expound on my own views here, encapsulated in the title of the paper I read: “Help My Country Bring Them Home: A Filipino Feminist Critique of the Neoliberal Transnational Care Regime.” The title is key, especially as I’ve been asked about it in at least three different occasions: During the conference itself, by my reactor, Dr. Sohoon Yi (Korea University); during a brown bag session with the graduate students and researchers of the ACWS; and during an interview with a journalist for The Kyunghyang Shinmun. I meant the title to harken back to my prior research on this topic, published in the online journal Kritike and entitled “When Your Country Cannot Care for Itself: A Filipino Feminist Critique of Care-Based Political Theories.” My talk at Ewha was intended for a primarily Korean audience, pertaining to what they could do to help, given the problem as I saw it. More than literally bringing Filipino migrant workers back to the Philippines, the phrase “bring them home” entails two levels of solutions, short-term and long-term. The easy one is to help them feel at home in their otherwise foreign environment, by advocating equal rights for them as enjoyed by Korean workers (in terms of wage levels, benefits, and legal protections), and perhaps a clear path to migration. The more challenging one is to transform the Philippines in such a way that its citizens never need to leave home just to survive. This means advocating policies that protect the local economy, creating jobs, negotiating more equitable terms for national debt servicing, working toward industrialization, and decreasing our dependence on (rather than lionizing!) labor export. (See in particular Ligaya Lindio-McGovern’s work, Globalization, Labor Export and Resistance: A Study of Filipino Migrant Domestic Workers in Global Cities.)

Care and women’s bodies: Works by Filipina artists at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul

As the only philosopher in the conference, I first felt out of place, worrying that my input might be a little abstract in comparison to others’ more practical ideas. I needn’t have worried; they all appreciated my key points about the need to re-value care, as well as to question the production-reproduction split. It was also a truly multidisciplinary gathering, as many research fields were represented: sociology, art and architecture, family studies, international development, women studies, queer studies, animal studies, communication.

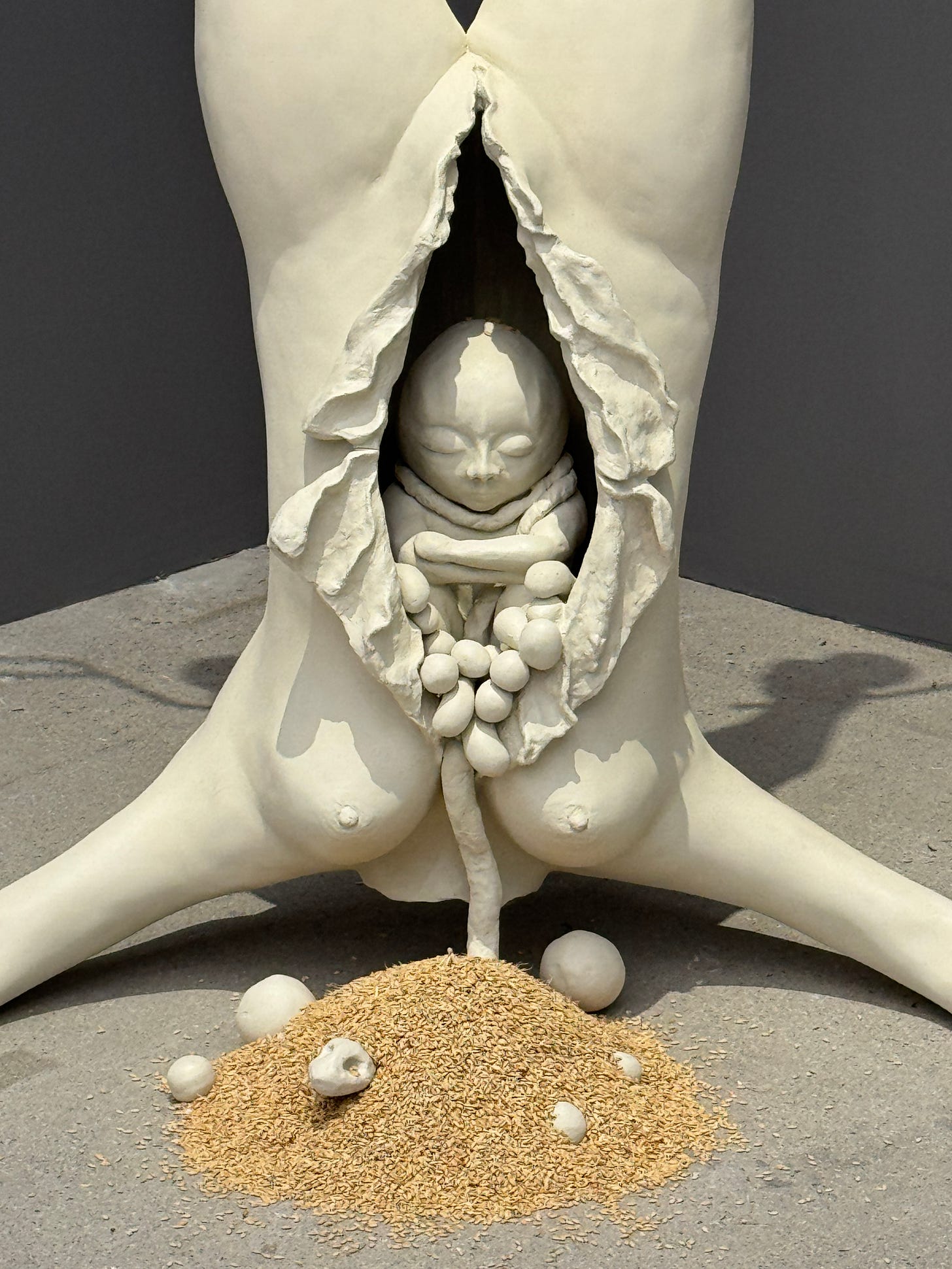

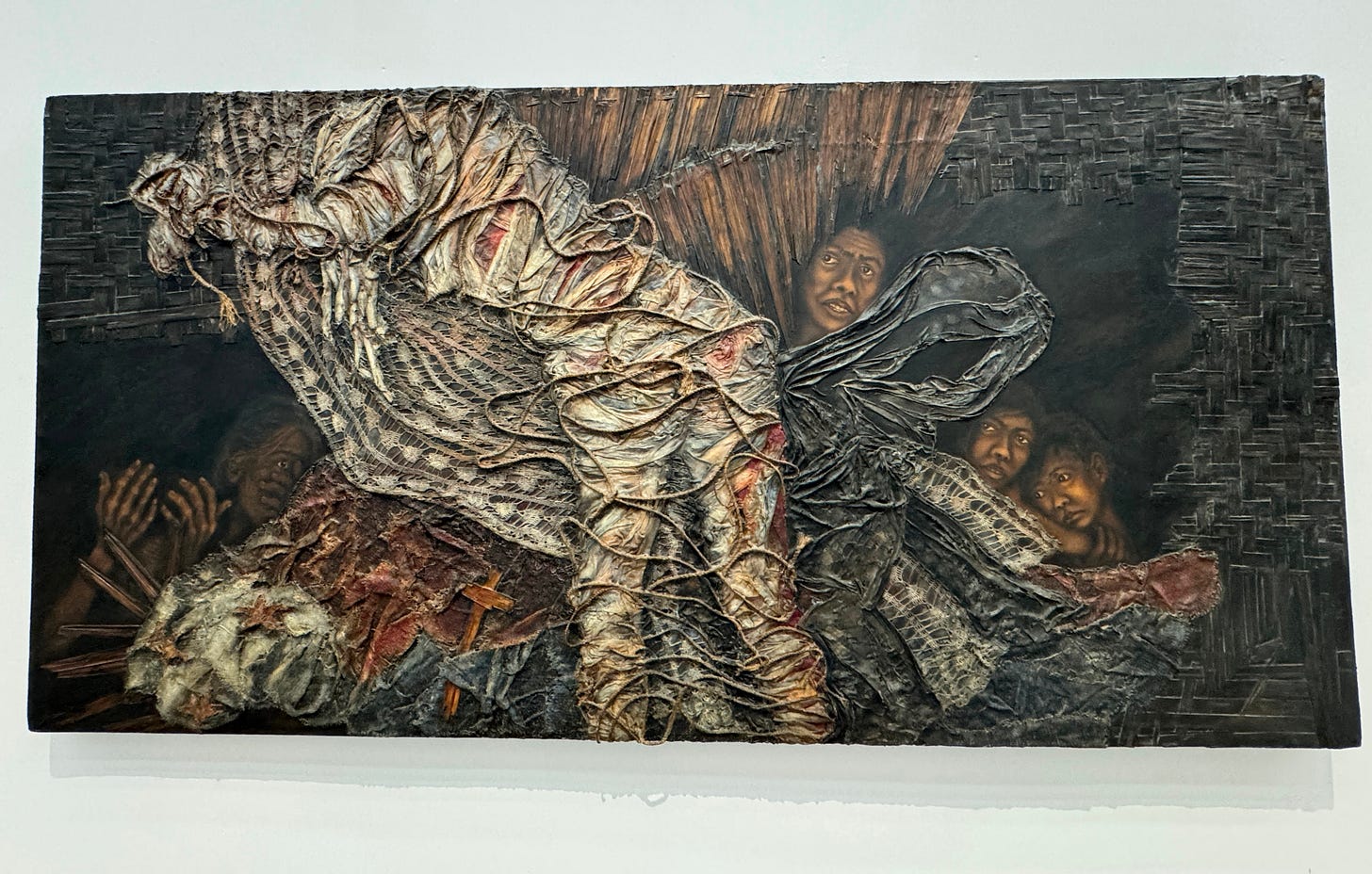

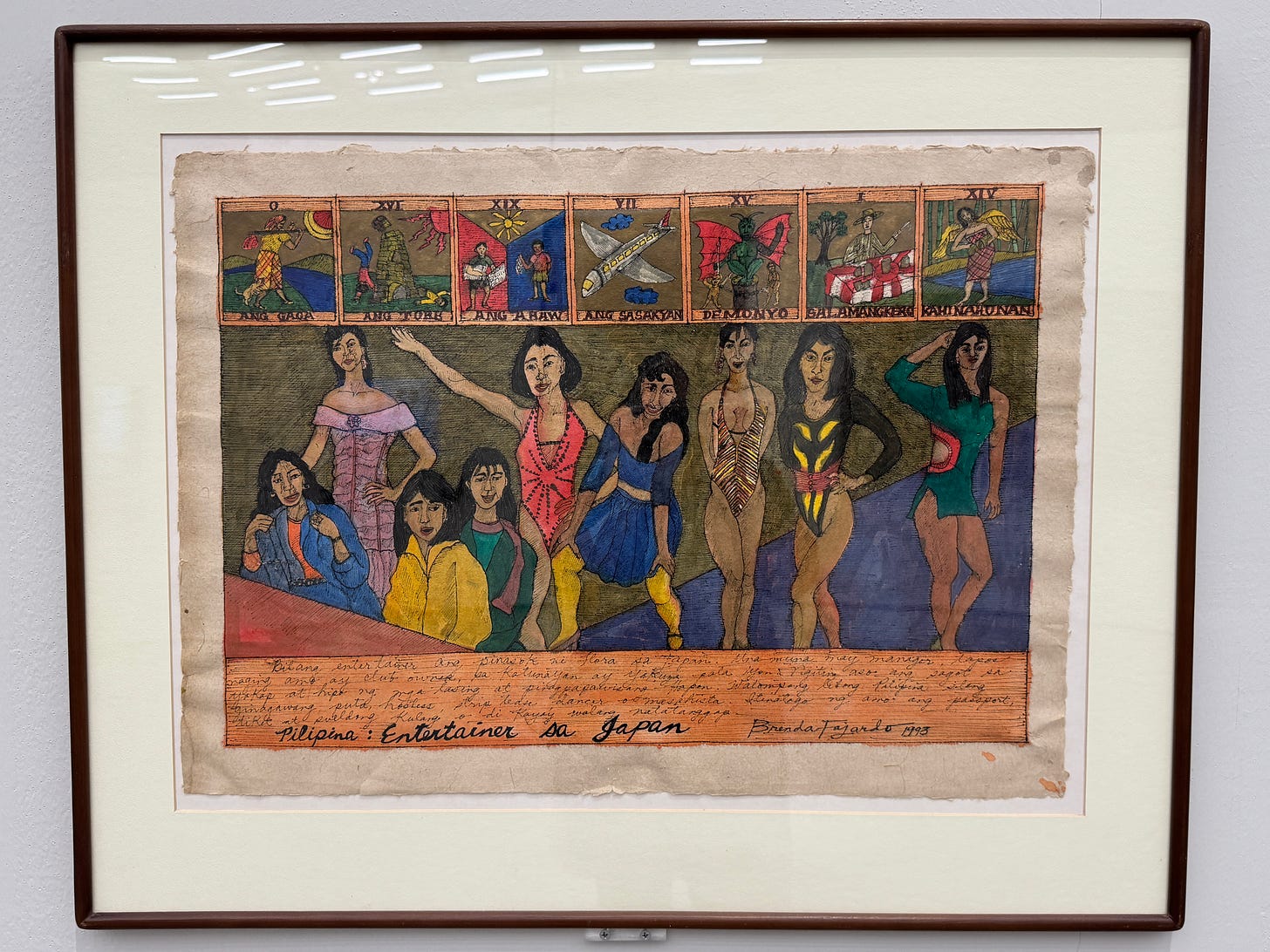

That the feminist critique of care can adopt many media was borne out by the exhibit entitled “Connecting Bodies: Asian Women Artists” at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul, which the conference organizers took us to see. Among the artists whose works are featured in the exhibit include Filipinas such as Imelda Cajipe Endaya, Brenda Fajardo, Agnes Arellano, and Pacita Abad. The following artworks struck me as particularly illustrative of the ways that care work has traditionally been seen as lowly work performed by women in the home, as compared to paid work in the public sphere. Even though it is the work of care that makes all other work possible, society doesn’t value it and the people who perform it. Through their installations, these artists show the struggle of Filipinas as patriarchy and capitalism enact violence on their bodies.

I was delighted to discover Arellano’s work at the museum, having first read about it in Amanda dela Cruz’s award-winning Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing thesis. Having read her collection of essays as a panelist for her thesis defense, I invited Amanda to share the opening essay in the Beyond the Ghetto newsletter, which we published in three parts. Her reading of Carcass Cornucopia is a powerful feminist take on a powerful feminist piece of art.

A safe space for women: Ewha Womans University

In addition to taking the conference speakers to see the “Connecting Bodies” exhibit, the organizers also took us to two lunches and a dinner. The lunches were more intimate, while the post-conference dinner included the graduate students and researchers of the ACWS as well as the reactors and panel speakers. In all of these gatherings, I kept thinking, It’s like we were of one mind! We get it. We get each other. Only Women Doing Philosophy has ever given me the same vibe.

Founded by American missionary Mary F. Scranton, Ewha is the first women’s university in Korea, and it remains an all-women institution (except perhaps for some male instructors). It is a beacon of resistance against the hierarchical and familialist ethos of Confucianism. I love how the Asian Center for Women’s Studies has its own building. Here, a brown bag session was held a couple of days after the conference, during which I served as the key resource person. Women from all over the world asked questions and shared their research projects. Many of them mentioned having read my previous work, and I felt so honored to have been able to inspire them.

Afterward, journalist Lim A. Young interviewed me for an article she was writing about the Philippine Domestic Helper Pilot Project. She showed me that she’d read the paper I delivered at the conference, which had been translated into Korean! During our conversation, Ewha graduate student Dounia Kourdi. acted as a very capable translator for us. Just like everyone else I met during my trip, Ms. Young agreed passionately with my sentiments, as we discussed the burden of care borne in different ways by Korean and Filipino women. She shared that as a mother of two small children, she experienced first hand the lack of support for Korean women when it comes to care work.

To cap off my last day at Ewha, Dounia and fellow graduate students Tala Wong and Louise Belleza gave me a tour of the campus. They were so sweet in undertaking this caring work of making a visitor feel welcome. This sort of institutional ambassadorship is often performed by women, usually junior academics. As someone who’s done my fair share of this, I felt doubly honored by their gesture. They and everyone else I’ve met, embodied the spirit of feminist solidarity. I couldn’t ask for a better welcoming party during my first visit to Korea.

Postcript: Caring men

After my trip to Korea, inasmuch as the dates coincided with the end of the first term at De La Salle University, I flew to Las Vegas to spend the Christmas break with my long-distance partner, B. (and later to see my sister, flying in from the Netherlands, and our parents who live in New Jersey). I am lucky to have caring men in my life. B. is not unlike my father, who routinely cooked the meals. My first morning back in Vegas, he made me his signature omelette, and afterward insisted on doing the dishes. I just sat at the table working on my laptop while waiting to be served! I suspect there are many men like him and my father who are redefining masculinity. One important consensus that emerged during my conference in Korea has to do with how male participation in care work is a key solution to the care crisis. The care crisis has emerged as more and more women joined the workforce; because care work continues to be feminized, they either take on the so-called second shift at home, or else pay women of a lower status to do the care work for them. We don’t need to live this way! Men can be our allies who are ready to eschew traditional gender norms in the name of equality. I know you neither expect my thanks nor acknowledgement, but please know that you are appreciated!