In this issue, we share the text of Jean Emily Tan’s lecture presented at the 20th Ateneo National Writers Workshop, in which she philosophizes about the nature and importance of creative practice as praxis. Presenting the narrative of the twin founding of BTG and Women Doing Philosophy (WDP), Tan writes of the key role played by a community of outsiders in shoring each other up and finding creative ways to change the world.

Good afternoon, everyone.

I am very grateful to the Ateneo Institute of Literary Arts and Practices (AILAP) for this invitation to speak before you, and truly honored to be welcomed to this space of creative writers. The invitation that I received from Christian Benitez was truly unexpected—and I feel, perhaps undeserved. I only decided to say yes when he explained that I could talk about my work with Beyond the Ghetto (BTG) and Women Doing Philosophy (WDP).

I shall not talk about the craft of writing of research or tips on conceptualizing research across disciplines, although I do think that what I will share falls well within the ambit of the “essayistic spirit” and “traversals” of “the critical and the creative,” if not of “the scholarly and the poetic,” the guiding themes of this writers’ workshop.1 I’ll be talking about some of my experiences and sharing some discoveries as I thought about these experiences. I hope at least some of what I’ll share will be of use to you in your own critical and creative practices.

Half-life

In radioactivity, according to Brittanica, half-life is “the interval of time required for one-half of the atomic nuclei of a radioactive sample to decay (change spontaneously into other nuclear species by emitting particles and energy), or, equivalently, the time interval required for the number of disintegrations per second of a radioactive material to decrease by one-half.”

Retracing the associative trail that led me to this word, it must have begun with the number 50.

Fifty. 50%, 50-50, the ratio of indeterminacy and chance. Half measure, midway, midlife. Fifty years old. But it wasn’t turning 50 that I was pondering. What I was taking up—the question I am living through—with the word half-life was the idea of going past 50. How am I discovering and practicing creativity past 50?

When I started thinking about what to share with you—before the word “half-life” rang in my ear—I knew I wanted to think about time. The quality of time of the creative life. As if it were an object of our doing, we often speak of finding time, making time. But we also speak of time sweeping past us, time slipping by, time spiraling or stopping. With “half-life,” I am thinking of being undone by time.

Past 50…. I’m thinking of the passage—this moving past the point of equilibrium. I’m thinking about the time of breaking down: the “interval of disintegration to one-half,” the time of disintegration, of decay. Half-life.

It’s interesting that in the definition I cited above, the parenthetical explanation of decay reads: “change spontaneously into other nuclear species by emitting particles and energy.” As my non-physicist mind understands it (or imagines it understands it), if you were an atom, by shedding parts of yourself—particle and energy—you slip into being another kind of atom, you are now defined as another “nuclear species” or “nuclide.”

When we disintegrate, when we break down, this process of decay is a process of emission. We expend energy—light, heat, sound. Words, images, stories, movement, music. Energies that reverberate in other bodies and minds, individual and corporate.

Past-fifty, I am thinking about how the movement of ripening is also the movement of decay….

Pandemic

I turned 50 at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. So many things happened during the time that many of us—at least those among us privileged enough to keep a living while staying home—were forced into a life of semi-isolation. “At the wake of the pandemic” is a phrase that can only be heard with an ellipsis trailing after it. I suspect many of us are still reeling in the aftermath of all the losses suffered and changes undergone, that it is difficult to speak about these in any straightforward way.

If there were a simple story I could tell about my half-lifing (my nucleic life shedding), one such story would be this: During the pandemic, I bleached my hair blond and colored it pink. When the pink faded, I had it dyed blue. At various times, while I grew out the bleached hair, I would touch up the fading dyes by apply colored conditioners—purple and then later, some kind of denim blue.

Maybe being online rather than meeting people in person gave me some courage—I must have felt less exposed. But why did I do it? It was such a frivolous, irrational act—possibly the last thing my colleagues expected of a middle-aged philosophy teacher of the motherly type.

I suppose you could say I went crazy at that time. I still had a good part of my hair dyed blue (or bleached blonde) by the time we began holding classes onsite. I walked around with my head screaming my pent-up rage and heartache over everything that I was going through in my professional life. My full head of hair—I imagine, like the head of those troll dolls that were popular in the ‘90s—could do all the screaming for me, without me having to say a word.

When I started to write this essay, I did not think I would end up writing about bleaching and dyeing my hair. But thinking about “undoing and being undone” and how these relate to creativity brought it to mind. You, artists, creative writers, you all know what I am talking about. The work that you do with words is woven with, supported by, fed by, and are in tension with the things you cannot explain or understand but embody and feel in your body, and encounter in your dreams. Our longings and dissatisfactions are already throwing windows open—our souls leaning over, testing how far we can go without falling—before we understand that we are heading towards a threshold that we would someday cross.

The work that you do with words is woven with, supported by, fed by, and are in tension with the things you cannot explain or understand but embody and feel in your body, and encounter in your dreams. Our longings and dissatisfactions are already throwing windows open—our souls leaning over, testing how far we can go without falling—before we understand that we are heading towards a threshold that we would someday cross.

BTG and WDP: Throwing windows open, creating new spaces

As an adult, you could say I was born and raised in the Ateneo Philosophy Department. I graduated from the AB Philosophy program in 1991, in my senior year the ed-in-chief of Heights.2 After graduation, I was hired by Dr. Soledad Reyes to teach in the Filipino Department, where I learned from Ma’am Beni Santos and DM Reyes. After a few years, I began my MA in Philosophy and would soon leave the Filipino Department to join the Philosophy Department.

This is another sense of “half-life.” I suppose you could say I have for a long time been straddling two realms, but somehow never managed to find my tribe. Two years ago, in the middle of the pandemic, I left the Philosophy Department and asked to be moved to the Interdisciplinary Studies Department. With IS as my home department, I now also teach in the Political Science Department and (though not currently) in the Philosophy Department on a part-time basis. Much of the thoughts I am sharing with you this evening about creative praxis has that departure as their background.

The creative practices and projects I am currently engaged in and the creative praxis I am seeking to articulate here are profoundly connected—in more or less direct ways—to this event, this fission in my life.

In changing departments—quite literally traversing institutional disciplinal boundaries—it has become very clear to me that our intellectual work, rooted in our lives and memories, is intertwined with the lives of others and with the lives of institutions. Our self-conception, our understanding of our place in the discursive spaces we inhabit, our estimation of the value of our words, whether they are worth saying, to what purpose, for whose ears; what questions are allowed and what are proscribed. All these are shaped within and in response to institutional arrangements and cultures that both enable our capacities and inhibit possibilities.

Our self-conception, our understanding of our place in the discursive spaces we inhabit, our estimation of the value of our words, whether they are worth saying, to what purpose, for whose ears; what questions are allowed and what are proscribed. All these are shaped within and in response to institutional arrangements and cultures that both enable our capacities and inhibit possibilities.

Writing this now, it all seems obvious and commonplace. And at some gut level, I must have known this for a very long time. Even as a young woman in the Philosophy Department, I always knew I had a chip on my shoulders. I didn’t know how to take compliments—I think I still don’t. I often sensed I was defensive and insecure, and felt compelled to prove my worth. But it took me a long time to really diagnose my feeling of alienation and to recognize and to put a name to my marginality and subordination in the world of philosophy.

It takes a long time, and it takes a crisis, a falling-out—to continue with our radioactivity metaphor, something of a fallout—for someone so thoroughly immersed in a culture to recognize fissures and to name contradictions in the world they inhabit.

In my case, it took student protests against sexual harassment, the fallout of young faculty members and even a graduate student being pushed out of the department, and most of all, the impenetrable wall of silence that the “band of brothers” built around the question of gender and power to finally bring me to the point of leaving the place that had formed me longest into the person I now am.

I couldn’t breathe. My speech, my protests were met by a silent void. I needed to find a space of freedom and possibility. When the pandemic broke out, throwing us all off course, uprooting us from the physical habits of daily working and living, the circumstances made it impossible not to ask in earnest about what possibilities could be realized, what untested paths could be taken.

* * * *

Interlude

Joy Harjo, a Native American poet, writes this in her memoir, Poet Warrior:

I am obsessed with maps and directions. The key to my internal map appears to read something like this:

East: A healer learns through wounding, illness, and death.

North: A dreamer learns through deception, loss, and addiction.

West: A musician learns through silence, loneliness, and endless roaming.

South: A poet learns through injustice, wordlessness, and not being heard.

Center: A wanderer learns through standing still.3

* * * *

In the shift to online spaces, webinars started to become a thing. I gathered my women colleagues at the Philosophy Department (I hadn’t left it yet at that time), some of whom I had not (and still have not) even met in person because they were hired during the lockdown. I envisioned a series of webinars that we women philosophy teachers would give as a teaching resource for use of other philosophy practitioners as well as a newsletter that would land in the mailboxes of interested individuals. I created a Gmail account for Beyond the Ghetto and released the first newsletter announcing the project in January 2021. (It was also a piece on Martha Nussbaum’s reflections on anger.)

Here’s a portion of what I wrote in that inaugural email:

Put simply, the goal of the project Is to increase the participation and presence of women in philosophy by introducing the works of women philosophers to teachers of philosophy, so that they may be encouraged to include more of these works in their teaching of philosophy. […]

There are too few women in the field of philosophy, to begin with, and even fewer working in the field of feminist philosophy. On one hand, women philosophers working outside the field of feminism are marginalized in philosophy; on the other hand, feminist philosophy has something of the status of a ghetto in philosophy – confined mostly to women – rather than seen as a legitimate area of philosophic inquiry. For the most part, feminist questions are thought to concern only women – meant to advance women’s interests – rather than posing questions relevant to everyone and to philosophy at large.

Too few women authors are included in the reading lists of philosophy courses, except in courses on feminism. But women certainly have much to say. And feminist thought cannot be said to have succeeded in its critical and political intent unless women philosophers were heard beyond the confines of feminism, and unless feminism and feminist questions were seen as a source of insight and a perspective that is relevant to broader philosophy.4

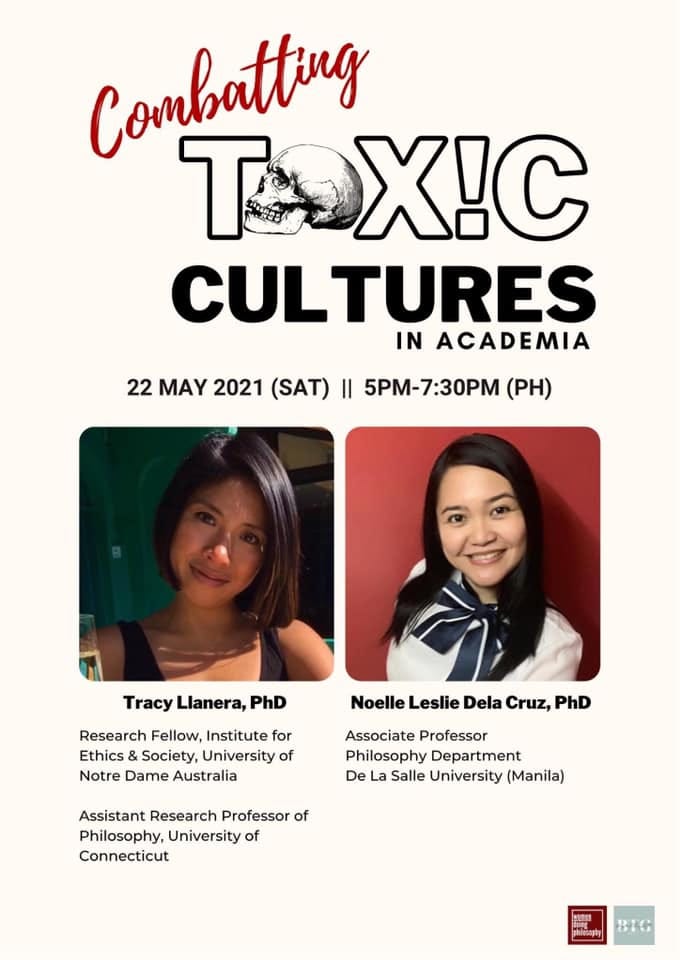

That first year, we held seven webinars, each of which had two speakers. One of these webinars, “Combatting Toxic Cultures in Academia,” delivered in May 2021 by Dr. Tracy Llanera, affiliated with the University of Connecticut and at that time a research fellow at the University of Notre Dame Australia, and Dr. Noelle Leslie Dela Cruz, affiliated with De La Salle University, was a watershed event in the life of WDP. Being able to give voice to shared experiences of oppression, to express compassion, and to form bonds of solidarity unleashed tremendous hope and immense creative energies.

After running BTG for a year, I passed on the leadership to my colleague Les Dela Cruz, (the same Leslie I mentioned above), a Professor of Philosophy and a Palanca awarded poet. She is still leading our little group of volunteers that is BTG. Just last week, in our third year, we held our 16th webinar and are about to publicize the upcoming 17th, the fourth in a series of webinars delivered by members of a research group working on their project called “The Philippine Condition: Threads of Critical, Decolonial, and Feminist Contentions.”

The webinars have morphed in time, depending on the interests and working projects of WDP members who have pitched ideas for webinars. In 2022, Les introduced another series of BTG events: Bluestocking, reading group discussions on works by women philosophers.

I cannot talk about BTG without also talking about WDP (Women Doing Philosophy).

At around the same time that I was dreaming of BTG, something else was being born. Activities were being organized in overlapping circles—I’m lucky to have been included in all three of them. In July to August of 2020, there was the reading group on a contemporary, award-winning book, Kate Manne’s Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, organized by colleagues from UST, Dr. Marella Bolaños and Dr. Darlene Demandante, who had the year before co-edited the special issue of Kritike: An Online Journal of Philosophy entitled “Women and Philosophy: An Initial Move Towards a More Inclusive Practice of Philosophy in the Philippine Context.”5 Wrested from our physical engagements in our own university work spaces, we found in our on-line gatherings a space to talk about our shared experiences of sexism and misogyny in our various professional settings—and to talk about these in a highly conceptual plane.

At around the same time, in July 2020, Cassandra Teodosio, a faculty member of the Philosophy Division of UP-Los Baños, and Danna Aduna, who used to teach at the Ateneo philosophy department, organized a meet-and-greet among interested women philosophers. Both organizers were junior faculty members in their departments. Neither had a PhD. Under the leadership of Cassie Teodosio, this group would become Women Doing Philosophy. WDP successfully held its first (and first of its kind in the Philippines) conference and workshop on the theme of Resilience, two weeks ago in UP-LB.6

Back in December 2020, during our first online holiday party and planning meeting, when WDP called for project proposals, I proposed BTG. Thus, what I started with my own close network of colleagues quickly found its lifeblood in the wider network of women philosophers affiliated with different universities as well as those—like my friend Danna—who would leave their philosophy departments.

* * * *

Interlude 2

Again from Joy Harjo:

We are all here to serve each other. At some point we have to understand that we do not need to carry a story that is unbearable. We can observe the story, which is mental; feel the story, which is physical; let the story go, which is emotional; then forgive the story, which is spiritual, after which we use the materials of it to build a house of knowledge.7

* * * *

Needless to say, I am not a digital native. I have resisted—through sheer inertia—the migration to social media. I still don’t have a Facebook account, have never used Twitter or Instagram. I don’t see this as a virtue, and confess this with embarrassment. I know that at some point, I may have to cave to external pressure and make the effort to learn to climb onto these platforms.

I’m something of a social media parasite—somehow catching information secondhand from friends and colleagues who are much more adept with the use of social media. By nature an introvert, my inclination is to stay (or disappear) in the background. The only thing I could imagine to do with BTG, when I started it, was to send letters that would land in mailboxes. The early issues of BTG were sent from Gmail. So old-school. It took the urging of colleagues—I wish to mention one, particularly, Von Katindoy —to move BTG to Substack. It is Leslie Dela Cruz, who manages our publication in Substack. She does—and has done from the beginning—the layout and picks the photos and artworks for the newsletters, posts announcements, and manages our archive. Though I still take care of copyediting the newsletters—and occasionally writing them—it is now Les who leads and inspires us at the helm of BTG.

I am reminded now—perhaps because my elder son is a Jurassic Park buff—of the famous Jurassic Park quote: “Life finds a way.” Despite my disinclination to publicity, because I felt I could no longer flourish in my accustomed environs, and perhaps because I had an intimation that I would soon no longer be able to teach philosophy courses in the classroom as I had long been used to, I found myself doing some version of public philosophy.

Despite my disinclination to publicity, because I felt I could no longer flourish in my accustomed environs, and perhaps because I had an intimation that I would soon no longer be able to teach philosophy courses in the classroom as I had long been used to, I found myself doing some version of public philosophy.

Looking for a new space in which to be, I ended up allowing myself to speak in a voice I was comfortable in. I wasn’t—and still am not—comfortable speaking as an expert. I didn’t want to give pronouncements about issues or dispense expert opinions from the philosopher’s pulpit, so to speak. But I could write letters and share my discoveries—articles, essays, books, YouTube lectures by women philosophers—to interested readers. Inspired by Jami Attenberg’s Craft Talk Substack letters8, I figured that I could share my thoughts to others whom I thought of as friends. I could pose questions—the philosophical skill par excellence—and suggest avenues of thought.

Without quite intending it, I found myself practicing my profession by addressing myself to a broader public, in the process opening up a new space and inviting others to join me in that space.

To borrow J. Harjo’s words once again, “We are all here to serve each other. At some point we have to understand that we do not need to carry a story that is unbearable.” I was using the materials of my struggles to build with others “a house of knowledge.”9

Para-academic

What sort of space is this house of knowledge that we are building? Writing this essay has given me the occasion to ask this question. And to come up with an answer. I would call BTG a para-academic space.

According to the trusty Dictionary app on my computer, this prefix para- which has the root meaning of “beside, adjacent to” can function in at least four interrelated, but distinct, senses:

distinct from, but analogous to: paramilitary | paratyphoid | paraphrase.

beyond: paradox | paranormal | parapsychology.

subsidiary; assisting: paramedic | paraprofessional.

Medicine denoting a disordered function or faculty: paresthesia.10

It seems to me that BTG is para-academic in all these senses. It is distinct from the space of academic departments and publications; its intent is to go beyond the strictures of women’s subordination and marginalization; it is meant to subsidize the teaching—and as it would later turn out—the research efforts of philosophy professionals. And—with a laugh—I grant that even the medical sense of “denoting a disordered function or faculty” can apply. I suspect BTG is something of a thorn in many a misogynistic philosopher’s side. (Women philosophers, after all, are still considered within the profession as something of an aberration.) We could say that in the manner of a symptom, the very existence of BTG calls attention to dysfunctions in the academic field.

I suspect BTG is something of a thorn in many a misogynistic philosopher’s side.

On experimentation: Reflecting on a myth of “knowledge production”

In the “essayistic spirit” of this writers’ workshop, I’d like to mention my ongoing attempt at experimentation with [or at] the boundaries of scholarly practice. I am currently undertaking a collaborative autoethnographic research project on “Gender Justice and Emancipatory Pedagogy” with Dr. Rachel Sanchez, from the Ateneo Theology Department. To quote our project proposal, our study seeks to examine “the realities and challenges faced by teachers in enacting feminist and emancipatory pedagogical principles in college courses.”11

This research project is new to me on many fronts. It is my first foray into collaborative research and writing. It is also my first research project that uses empirical methods, going beyond the traditional borders of textual philosophical research and stepping into social science research. Moreover, autoethnography is itself a research method that contests the presuppositions of traditional ethnography.

Part of our research methodology consists in keeping journals about our teaching experiences. This is one way by which we record and collect our experiences—our thoughts, impressions, feelings—so that later we would be able to systematically examine and dive into them, reflecting jointly upon our experiences to see how these intersect and might be situated within—and thus illumine—broader social, institutional, and political realities.

The process of transcribing and coding my journals brings to mind a phrase from

Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals: “honey-gatherers of the spirit.” Nietzsche uses the metaphor to refer to “men of knowledge” who unavoidably misrecognize themselves. In the Preface to the Genealogy, Nietzsche writes:

We are unknown to ourselves, we men of knowledge—and with good reason. We have never sought ourselves—how could it happen that we should ever find ourselves? It has rightly been said: “Where your treasure is, there will your heart be also” [Matthew 6:21]; our treasure is where the beehives of our knowledge are. We are constantly making for them, being by nature winged creatures and honey-gatherers of the spirit; there is one thing alone we really care about from the heart—”bringing something home.” Whatever else there is in life, so-called “experiences”—which of us has sufficient earnestness for them? Or sufficient time? Present experience has, I am afraid, always found us “absent-minded”: we cannot give our hearts to it—not even our ears! Rather, as one divinely preoccupied and immersed in himself into whose ear the bell has just boomed with all its strength the twelve beats of noon suddenly starts up and asks himself: “what really was that which just struck?” so we sometimes rub our ears afterward and ask, utterly surprised and disconcerted, “what really was that which we have just experienced?” and moreover: “who are we really?” and, afterward as aforesaid, count the twelve trembling bell-strokes of our experience, our life, our being—and alas! miscount them.—So we are necessarily strangers to ourselves, we do not comprehend ourselves, we have to misunderstand ourselves, for us the law “Each is furthest from himself” applies to all eternity—we are not “men of knowledge” with respect to ourselves.12

I have long loved this passage from Nietzsche. One sometimes thinks it’s too beautifully written to belong to philosophy. With such turns of phrase as these—“each is furthest from himself” (which harkens back to Heraclitus), and “honey-gatherers of the spirit”—I could almost forgive Nietzsche for his misogyny. Almost.

But now, as I seem wont to do these days, I re-read the passage as a woman philosopher, a little outside the borders of the academic discipline, from my recent experiences with fellow Women Doing Philosophy. I find myself able to name something discordant about the metaphors in this passage.

Something I am only realizing now: this is the image of the philosopher that has guided me for a long time—the solitary, absent-minded figure, so immersed in his work, so immersed in himself, working alone in his library, writing his books. Mystified by his own works, perhaps surprised at his own greatness. Nietzsche mocks this figure, who misunderstands himself, and yet, and yet, does he not also look upon the folly of this “man of knowledge” with a certain air of indulgence?

But if we were really bees, “honey-gatherers of the spirit,” would we be solitary creatures “divinely preoccupied and immersed in himself”? It is true—and I concede this to Nietzsche—I am often very self-centered and my vision can be pretty myopic. And yet, I’d have to say, that that image of the philosopher—and need I say that this philosopher in my mind’s eye is male?—has done more to prevent me from writing creatively and thinking courageously than it encouraged me to come to my own as a philosopher.

These past three years, I discovered that my solitude needs companionship. One practice that has helped me was the shut-up-and-write sessions (SUAWs) that have become more or less a staple in my life. I need the friendship of others with whom I could bounce off ideas, from whom I can learn of philosophical work in areas beyond my knowledge, with whom I can share my thoughts, my woes, and perplexities as well as my knowledge.

I need a supportive community. My creative work happens slowly, simultaneously, in between many interruptions. Many ideas and inspirations take their time, working in their subterranean way, looking for the right moment to surface, waiting for collaborators and conversation partners, because the life of ideas surpasses individuals—in their origin as well as in their intention, in their matter, as well as in their form.

I need a supportive community. My creative work happens slowly, simultaneously, in between many interruptions. Many ideas and inspirations take their time, working in their subterranean way, looking for the right moment to surface, waiting for collaborators and conversation partners, because the life of ideas surpasses individuals—in their origin as well as in their intention, in their matter, as well as in their form.

These past three years have taught me that finding one’s voice is not a solitary process. The struggle to find one’s voice is not just a struggle for authenticity but also a struggle for recognition.

On the praxis of the undone

As I am sure you have noted, the pairing of “praxis” and “undone” is meant to be paradoxical, since “praxis” is rooted in the Greek prattein— to do. In this penultimate section of my lecture, the term “praxis” will recede into the discussion of undoing and of the undone. But before I turn to an elaboration of “undone,” a word about “praxis.”

I could have used the term “practice,” but I wanted to keep its Marxist inspiration. In particular, I want to highlight this idea: as researchers, creative writers, intellectuals, artists, we do not only produce artifacts. For better and for worse, we produce and reproduce social relations and forms of life.

When we tell our stories and receive the stories of others, whatever we do with them—whether we honor or ignore them, understand or misinterpret or erase them—we are building collective spaces. We do and undo ways of being with ourselves, with others, with the natural world, with our social and institutional contexts.

As to the word “undone” in “the creative praxis of the undone,” when I placed this word in my lecture title, I was thinking of these semantic associations: to have been undone by an experience—unsettled, shaken up—the loosening of ties.

“To be undone” can mean utter destruction—as in “that was her undoing.” It can mean dismantling—which is to say, to uncloak; to remove the protective cover that holds a body together.

To undo, can also mean to oppose the effects of an action, to counteract. At the very least—turning to another sense of un-do—which is to not do—to counteract an action or a habit simply by not doing it anymore, perhaps by saying no or standing still or stepping out of the flowing stream.

When to undo pertains to undoing harms, to undo is to engage in acts of healing. Undoing then is the paradoxical way towards wholeness.

There is also “undone” in the sense of “not yet done.” Work not yet done can either mean “not yet finished, awaiting completion” or “has not yet been attempted.”

A dream deferred. Or work begun but perpetually derailed. A project, many projects that have had multiple beginnings, various iterations (at least in your head), but time and again gets overtaken and temporarily forgotten.

Projects begun, with their end beyond sight…

Living in half-life

So, what does creative praxis look like from where I am standing at past-50? Let me end with these suggestions:

To half-life, to be mindful of our nucleic shedding, so to speak, is to be more mindful of the flow of our energies. To be more careful with our yeas and nays. [Dye your hair pink; you may reserve your yeses to those who can put up with it.]

Discovery entails some form of dismantling—some form of laying down our protective covers; some form of shedding and slipping into altered ways of being.

To live in half-life is to live a life of learning: There is no learning without unlearning. And we unlearn things by performing acts of resistance.

Finally. Life is short. It is always too short. It’s okay to begin something new even if you can’t see it to its end.

We are always—in any case—not yet done.

Call for Applications: 20th Ateneo National Writers Workshop. AILAP Facebook page, January 24, 2023.

Heights, now Heights Ateneo, is the official literary and artistic publication of the Ateneo de Manila University.

Joy Harjo, Poet Warrior: A Memoir (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2021), pp. 45-46.

Jean P. Tan, Beyond the Ghetto Newsletter #1, January 6, 2021.

Kritike (June 2020), Vol. 14, no. 1.

The Resilience Workshop for Women Doing Philosophy was funded by the University of Connecticut College of Arts and Sciences, through a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Grant awarded to Dr. Tracy Ann Llanera, and was co-sponsored by the University of the Philippines-Los Baños Philosophy Division.

Joy Harjo, Poet Warrior, p. 20.

Jami Attenberg is an American writer who runs the #1000wordsofsummer, an annual 2-week co-writing period, for an online writing community.

Joy Harjo, Poet Warrior, p. 20.

New Oxford American Dictionary

Jean P. Tan and Rachel O. Sanchez, “Gender Justice and Emancipatory Pedagogy” (a project proposal).

Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, translated by Walter Kaufmann and RJ Hollingdale, Preface 1 (Vintage edition, 1989), p. 15.