Dear Friends,

Stunned. Stumped. Stopped dead in my tracks.

The morning after election day, when the unofficial but incontrovertible count announced the election of Marcos, Jr. to our nation’s highest office, the image that occurred to me, capturing the sensation of dull heaviness in my gut, was of a mechanical watch, slowing down, about to lose all tension, the last tick, the last quiet sweep of the needle-thin second hand, and then full stop.

When I texted the news to my sister living abroad, she wrote back: “I have no words.”

I had words – but fragmented ones struggling to be formed, and I had no energy to piece them together to the point of clarity. In one of the conversations I had with my students last week, I was reminded of a lecture I delivered to the Philosophical Association of the Philippines in 2017. When I reread it, I realized that many of the things I wrote then, though said in a different context, are still relevant now and, refracted by the present moment, have even gained a new significance. I find that I wish to share those thoughts once again.

A while ago, I spoke of the image of the timepiece winding down. Let me now share with you a memory: of my grandmother setting her watch to time and then winding it again. The ritual of winding the clock was a kind of meditative practice figuring a hiatus – the interval of uncounted time taken as a chance to breathe, to take stock and find one’s bearings. Borrowing these words from my past self is my gesture of winding my clock, so that I might begin again.

Please pardon the length of this essay – it goes well beyond the limits of our regular newsletter.

Theses on Feminism

The task I have set for myself this morning is a humble one. What I am offering you is not a scholarly paper or an overview of the state of feminist scholarship in the Philippines. What I wish to do is to declare myself in some sense, to propose for your consideration some theses about feminism and, in particular, about what I take to be fundamental concerns and challenges arising from where we are — Filipino feminist thinkers and advocates — in the present moment.

I began by asking myself the question, “What can I say about feminism, on the presupposition that feminism is a live question?” For I am in no doubt that it is a live question.

What I am aiming for is not originality – but clarity and resonance. I hope that in being able to bring some ideas into focus, my thoughts could resonate with your concerns, insights, and questions, and thereby open for everyone here avenues of further research and examination with a view to enlivening feminist practices.

If I could state a series of theses that would evoke further questions, debates, and researches, what would say? These are what I came up with:

1. Feminism is about sex.

2. Feminism is not one.

3. Feminists need an image of praxis and thought: not marginality but interstitiality.

I. Feminism is about sex.

Feminism is not just about sex, but the questions regarding sex — sexual difference, sexual identity, sexual hierarchies, sexual roles and proscriptions, sexual pleasure, sexual intimacy, sexual violation — these are central to any feminist analysis of an issue or to any feminist activism.

It is possible, for instance, to frame feminist concerns as questions to access to public goods —for instance, education, employment — but one soon realizes that one cannot deeply address problems of access without contending with the roadblocks of sex. Sexual harassment compromises women’s success in education; sexual stereotypes (such as expectations of sexiness) limit career choices. The specter of sexual violence everywhere keeps women (and the sexually othered) in their place.

What follows from the thesis that feminism is about sex? What are the implications that follow depending on whether one treats sex as a question or a non-question?

1. The question of whether an alliance can be forged between feminists (as theorists and as advocates) and queer, transgender, and other non-traditional gender identities depends on whether sexual difference and gender are seen as questionable or not.

As long as one takes sex as a non-question — because sexual difference as well as the often attendant norm of heterosexuality is simply taken as natural — the scope of one’s feminist commitments end within the boundaries of heteronormativity and the privileged position of cisgendered women.

2. Sexual violence is a central question for feminism, and it has to be continually interrogated from multiple perspectives.

Sexual violence is not just a question of criminality and should not be viewed as a matter of deviance. We should inquire into the meaning of sexual violence and examine how it is both taboo and at the same time tolerated. (Or perhaps, it is precisely as taboo that it is tolerated.)

We need to ask, what is the relation between sexual abuse and the gendered division of reproductive labor? Why is the care of the young for the most part assigned – in addition to the mother – to daughters, female cousins, aunts, grandmothers? But not to sons, uncles, male cousins, grandfathers? Why are yayas female and not male? Is it just because we see males as hopelessly incompetent caregivers? Or is it because males are thought to be possible perpetrators of sexual abuse and agression?

It might be asked by some, whether feminism is still relevant in a society where female students actually outnumber male students. Whether, in a country where women have been elected or appointed into public office at the highest levels – President, Supreme Court Chief Justice, Ombudsman, Speaker of the House of Representatives – women still have cause to complain. For me, the answer is clear: As long as rape exists, feminists still have a lot to fight for and against.

3. If feminism is about sex, and sex is a minefield, a site of inscription of taboos, and is constitutive of our archaic and embodied sense of what it means to be human; if sex lies at the border of humanity and animality; if sex, being crucial to the continuation of the human species, straddles both the natural and cultural reproduction of human beings; then feminism requires anthropological studies.

An important area of feminist study would be anthropological research inquiring into the deep historical roots of misogyny and patriarchy particularly in Filipino societies and cultures.

I have occasionally heard it said that Filipino society is matriarchal. I suspect that in their own family lore, hardly any family would be unable to point to a matriarchal figure in their history, or would be unable to name what we call “strong women.” But we have to ask, does this warrant the label “matriarchal”? (And in any case, would matriarchy—conceived as a mere reversal of patriarchy—be any more desirable than patriarchy? I don’t think it takes much to realize that what feminism aims for is the liberation of women and not the subjugation of men.) Is it true that by virtue of the figure of the “strong woman,” Philippine culture could be considered matriarchal?

3.1 On the babaylan

Feminist historical studies have brought to our attention the figure of the babaylan (or katalonan) as a valuable resource for feminist theorizing and practice from a Filipino perspective. While Sr. Mananzan would not go so far as to say that it was matriarchal, she does point out that pre-colonial Philippine society was considerably more egalitarian in its treatment of men and women:

Though the pre-Spanish society cannot be characterized as matriarchal…. [w]e saw the equal value given to female offsprings. We have described the participation of the woman in the decision-making processes not only in the home but in the important social processes of the bigger community.

There is, I believe, persuasive evidence that misogyny and patriarchy are to a large extent a legacy of our colonial history. Nevertheless, I think this notion still requires a great deal of examination.

Is it true that patriarchy is only (or largely) a legacy of Western colonialism? And if it is, what would this historical fact mean for us here and now? Would it not mean bringing to the center of our academic research and, more importantly, to the forefront our political, economic, and social engagements the voices, histories, traditions, interests, rights, and practices what remains of our indigenous cultures and communities?

What is the meaning of the Babaylan in our history? It seems to me that the babaylan is a powerful figure which can inspire creative appropriations for liberating practices. But lest we get caught up in a nostalgic mystification of a figure stripped of her historical anchoring, we need to examine the social meaning of the babaylan. What sort of social arrangements (social, political, cosmological, psychological, and religious) gave rise to the babaylan?

When Zeus Salazar names the traditional figures of power in the barangay as the datu, the panday, and the babaylan, feminist scholars are quick to latch on to the remarkable notion that in pre-Hispanic Filipino society, women were actually held in high esteem, and that they peformed a central social function. Salazar writes:

Noong panahong dati, ang babaylan ay bahagi ng isang istrukturang panlipnan at pang-ekonomiya na umiikot sa gawain ng tatlong sentral na personahe—ang datu, and panday, at ang babaylan o katalonan mismo.

[….]

Ang datu ay para sa aspektong militar at pang-ekonomiya, at ang panday naman ay para sa aspektong teknolohikal.

Ang pangatlong ispesyalista ay ang babaylan mismo. Ang babaylan ay napakainterasante, sapagkat siya ang pinakasentral na personahe sa dating lipunang Pilipino sa larangan ng kalinangan, relihiyon, at medisina at lahat ng uri ng teoretikal at praktikal na kaalaman hinggil sa mga penomeno ng kalikasan. Sa madaling salita, proto-scientist ang babaylan, sa kabila ng kanyang pagkadalubhasa hinggil sa tao at sa diyos.

Without minimizing the significance of the babaylan, we have to ask – the rare and contested mention of female rulers notwithstanding – what does it mean that the datu and the panday were predominantly males? How did it happen that the datu and the panday did not disappear under the new dispensation whereas the babaylan did? How did it happen, through what processes, through what historical turn-arounds, through what genealogical reinterpretations did it come about that the words “datu” and “panday” have not been consigned to linguistic oblivion the way that the words “catalonan” and “babaylan” have?

Was it only an unfortunate accident of history that the loss of the old religious function, when overrun by the new religion – which introduced an alien misogyny – led to the extinction of the old priestesses? But shouldn’t we also ask what the gendered division between datu and panday on the one hand and babaylan on the other means?

In other words, was there perhaps already an incipient hierarchical division of social labor between the genders in our pre-Hispanic social arrangements, that the advent of Christian colonialism exploited and exacerbated? What does it mean that political power and technological knowledge resided in men and religious ritual and cultural memory in women?

Of course, it is important not to oversimplify this dichotomy. It has been pointed out, for instance, that the babaylan’s wisdom served to guide not just what we would in our time call spiritual matters and that she provided guidance on matters of the community’s economic life – for example, the babaylan was consulted about when to begin planting. Nevertheless, broadly speaking, what is at stake – it seems to me – is not just the division of roles assigned to men and women, but – equally problematic – the resulting subordination of cultural and spiritual wisdom (on the one hand) to technological and political power (on the other).

Thinking about the babaylan, I wonder if the extinction of the babaylan has a more profound effect on our communal psyche – namely, our tendency towards communal amnesia. If the babaylan was indeed the memory keeper, and we lost her somewhere in our history, it is perhaps not surprising that we as a people have such a short memory. Perhaps for women to resurrect the babaylan is for her to perform the function of historian, of archivist, of story-teller, of memory-keeper.

3.2 Examination of kinship structures

What is it about our society that makes us relatively progressive when it comes to women’s inclusion in the wider society?

In the UN Human Development Indices of 2018, the Philippines scores amazingly high in the Gender Development Index, despite the fact that we perform poorly in many indicators (notably, those that relate to reproductive health and labor force participation). What accounts for our good Gender Development Index score? Two things: (1) Our relatively high percentage (still low, compared to men, but better than in other nations) of women in parliamentary seats, and (2) the greater number of years of schooling for females than for males.

Our women stay longer in school than their male counterparts, but oddly enough, this does not translate to greater economic participation. What are we to make of this? What do we educate our women for? And what does this say about our educational system? Is it perhaps the case that females in general do well in school because their obedience is rewarded by the academic regimen?

As to the other indicator (the relatively high percentage of women holding parliamentary positions), we would do well to ask, to what extent does the number of women politicians reflect gender equality? How much of women’s participation in elected office is attributable to their membership in political clans?

In other words, we need to ask, what are the limits of this apparently progressive inclusion of women in our country’s socio-economico-political life? How is it possible that our presumably “matriarchal” culture seems perfectly compatible with our patriarchal politics?

I think more studies should be done on the relation between gender equality, female empowerment, and our bilateral kinship structure.

I am curious to know, for example, whether there is a correlation between our bilateral kinship structure and the relatively egalitarian relationship among men and women in Filipino society. I suspect that the bilateral kinship structure manifested by our extended families that stretch out to both the maternal and paternal lineage exerts a countervailing force against the patriarchal family structure. But on the other hand, we should also consider whether, in our post-colonial patriarchal situation, this positive influence might be undermining a more intent, more serious, and more sustained resistance to patriarchy, by providing an avenue of easy accommodation and thereby facilitating the appropriation of the power and agency of women for the sake of consolidating the power of the patriarchal clan.

What is the relation between patriarchy and the politics of dynastic rule? Is a political system that is essentially feudal compatible with feminism? Or is a feminist politics essentially democratic in nature? It is not enough to ask whether women participate in politics; we also have to ask – in what ways? Are they perhaps only able to act (at least for the the most part) within boundaries and terms set by political dynasties?

(On this note, we should think about the militarization of the government bureaucracy from a feminist perspective.)

4. Feminism should interrogate the role of sex in politics. If feminism is about sex, then a feminist critique of politics has to ask about the role of sex – of the erotic – in our political life.

When Mocha Uson and Drew Olivar made that botched “Pepe-dede-ralismo” dance video, many criticized the duo for bringing a matter for serious political deliberation down to the level of crass entertainment. Others begrudgingly admitted (if not admired) their political astuteness in hitting upon what would have been a rather effective tool of propaganda. On the face of it, one could say that it was a politically astute idea to sell a political idea through sex; but I think that Uson and Olivar’s perspicacity is more radical.

I think that the genius of Uson and Olivar consists in their catching on to and making explicit something of the current political ethos, namely, the idea that tyranny is sexy. Inequality is erotic. And no one is turned on by equality. Democracy is patently un-sexy.

I think this is something worth thinking about. How are we socialized into sexuality? Are our models of eros relations of equality? Are we democratic in our sexual relations? Are our romantic ideals egalitarian or hierarchical?

Do we eroticize the silencing of women? In the political arena, is it perhaps the case that the attractive woman is presumed to be the silent woman? And women who just won’t shut up are sent to jail?

II. Feminism is not one.

Feminism, like all movements of emancipation, has a fragmented history involving a proliferation of forms with conflicting beliefs and self-conceptions. There is not just one feminism. We have to contend with different forms of the emancipatory project, from different localities and different times, each drawing various lines of resistance.

How do we reconcile the tension between, say, feminists of my generation, who criticize the objectification of women as objects of sex and feminists of a younger generation who see in their manner of dressing – what I – but not they – might call hypersexualized fashion – an expression of their sexuality and a claiming of their right to it?

What are we to make of this disagreement? Are these to be thought of as types of feminism? Are they compatible with one another? Or is it a matter of displacing (or outgrowing) one type with the other?

Perhaps we could begin to address this issue plurality and contentious diversity by accepting the radical (and possibly ineradicable) ambiguity of any gesture or cultural phenomenon. For instance, how wearing the hijab can be experienced as liberating, or how modesty of garb might be is experienced — not as (or not simply) as a mechanism of control of women’s sexuality — but as a means of maintaining a space of freedom from the sexualization of the body.

Contextualizing particular feminist gestures and commitments within their particular socio-cultural-historical milieu would allow us to recognize the fact that the struggle for autonomy and equality might take different forms in various contexts. In some socio-historical contexts, it might mean fighting for the right to go to school; in others cultures, say, in sexually permissive ones, it might mean claiming the right to speak about one’s sexual pleasure.

Intersectionality is an analytical framework that is particularly relevant here. It is a way of systematically naming axes of hierarchical differentiation and oppression that account for different forms of sexual oppression. Intersectional analyses allow us to understand the specificity of various experiences and stuggles of women.

Applied to the Philippine context, we can use intersectional analyses to ask questions such as these: How do the categories of gender and indigeneity intersect? How do forms of economic activity affect gender relations (and vice versa)? How do the differences, say, between agriculture and industry, between rural and urban, between service and information economy affect gender roles? What is the relation between gender and migration? Between gender and various forms of migration?

It is important to ask what it would mean for a woman in a farming community to be empowered as a woman. What does it mean for an OFW to be empowered as a woman? What does it mean for a female university student to be empowered as a woman? What does it mean for a housewife (homemaker) to be empowered as a woman? Does maternity mean the same thing to women of various classes? Of various religious and cultural backgrounds?

For a feminist, intersectional analysis is an important tool for self-criticism, because it serves as a corrective to our unavoidably myopic tendency to generalize and unreflectively impose our own ethical imperatives upon the agency of other human beings – women and also men.

And yet, having said this, the question remains: How are we to deal with the disagreements about feminist commitments, about various forms of feminism? I am thinking, for instance, of the fact that while I recognize that my cousin’s family could not have survived without her domestic labor, I have to confess to feeling a certain disappointment that she abandoned—note my negative choice of words—her career when she gave birth to her first child.

With regard to such disagreements, do we have nothing more to say to each other than that we tolerate other women’s choices that we ourselves would not make? We need to develop a way of thinking through these differences and disagreements.

I’m in search of something more than just the formation of strategic alliances in the sense of a temporary suspension of disagreements for the sake of advancing a common cause. (This approach might have its uses, but I find it objectionable because it reeks of the distasteful opportunism and violence of “your enemy is my enemy.”) What I have in mind, rather, is a broadening of our concern and a deepening of our understanding of other women’s situations, in order to develop creative ways of advancing the hard work of emancipation.

To borrow a Deleuzian inspiration, we need an image of thought, to spark our communal creativity. Which brings me to my last thesis –

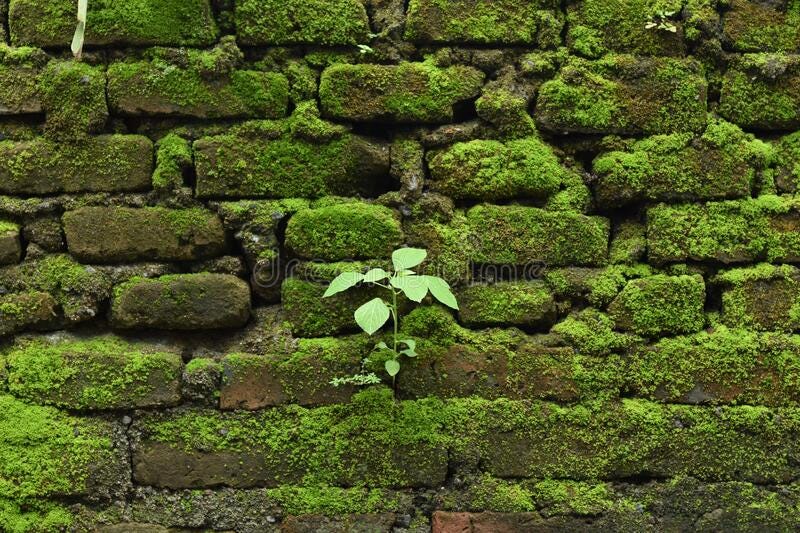

III. Feminists need an image of thought, and marginality is not our image; it is interstitiality: be like moss. [Or: feminism as an ethic of small spaces]

At this point, I’d like to share with you an excerpt from a podcast called “On Being.” In this part of the conversation between the host, Krista Tipett, and her guest, Robin Wall Kimmerer (a botanist who draws upon her indigenous American Indian heritage in her scientific practice), speaks about the wisdom of mosses:

When I think about mosses in particular as the most ancient of land plants – they have been here for a very long time, they’ve figured out a lot about how to live well on the earth and … they are really good story tellers in the way that they live. An example of what I mean by this is in their simplicity, in their power of being small, mosses become so successful all over the world because they live in these tiny little layers on rocks, on logs, and on trees. They don’t strive to be big and to be powerful; they work with the natural forces that lie over every little surface of the world. To me they are exemplars of not only surviving but flourishing by working with natural processes. Mosses are superb teachers about living within your means.

[….]

Mosses have -- in the ecological sense -- very low competitive ability because they’re small, because they don’t grab resources very efficiently, and so this means they have to live in the interstices, they have to live in places where the dominant competitive plants can’t live. But the way that they do this really brings into question the whole premise that competition is what really structures biological evolution and biological success. Because mosses are not good competitors at all, and yet they are the oldest plants on the planet. They have persisted here for 350 million years. They ought to be doing something right here.

And one of those somethings I think has to do with their ability to cooperate with one another, to share the limited resources that they have, to really give more than they take. Mosses build soil, they purify water, they are like the coral reefs of the forest. They make homes for these myriad of these cool little invertebrates who live in there. They are just engines of biodiversity. They do all of these things and yet they are only a centimeter tall.

How can we draw an image of thought for us feminists from the moss? The key notions I would like for us to ponder are these: small spaces, interstices – the in-between spaces across which we can extend our gestures of solidarity, cooperation, persistence.

How do we deal with the reality of a multiplicity of women’s experiences, concerns, commitments, and perspectives? I suggest that we expand both our theoretical inquiry and our practical engagement by locating areas of research and struggle wherever we might be, in whatever crevice we might find ourselves, or by going to speak with women we had not thought to listen to before. Bring the fight where it was not brought before – or where it is not being fought enough.

I don’t know if this is something that resonates with you, but as a woman, I find that I have come to internalize the mantra “pick your battles.” This is ambiguous. On a positive interpretation, this is the language of compassion. Because we know that everyone, including ourselves, has a sexist blindspot, and we understand that change takes time and not all at once, we often choose to let things slide.

But on a negative interpretation – which I now wish to highlight – “pick your battles” can be an excuse for accommodation. We learn to put up with the small humiliations because we tell ourselves there are more important issues – bigger abuses and interventions that need to be done on a larger scale.

But I think that rather than saying that we should pick our battles, we should say instead that no battleground is too insignificant for us to enter. We need to develop an ethic of small spaces. Our struggle is in the mundane, in the concrete, in the day-to-day, in the intimate quarters not often or heretofore recognized.

For instance, most of us here are in one way or another involved in academic institutions. We are involved in teaching. To ask about the future and the possibilities of feminism in the Philippines necessitates that we inquire not only about the presence of feminist courses in the curricula or about recruiting more women into the field. We also have to consider our pedagogical paradigms and ideals, in particular, our unexamined models of master-student relationships.

We have to ask ourselves – especially in a field that is dominated by men – whether the classroom is another site in which we reproduce the eroticization of hierarchy. Do we teach our students to be autonomous, to be independent thinkers and seekers. Do we encourage our students – women as well as men – to find their own voice, or do we seek and encourage their adulation?

Conclusion

If feminism were to be really fruitful, really revolutionary, theory and practice should be mutually enriching. On one hand, our interactions with ever-broadening ranges and contexts of experience should broaden and deepen our understanding of oppression – and among these, oppression based on gender. And on the other hand, deeper theoretical insight should expand one’s compassion and moral imagination.

I take this to be a litmus test of a feminist ethic: Do we respect the woman’s agency? Do we listen to her voice? Do we allow her space to tell her story? Or do we silence her?

Feminism is a pathos for solidarity. And by this, I mean, not just solidarity with other women, but with anyone who is oppressed. This is the point of intersectionality – not simply to diversify our understanding of women’s experiences of oppression, but to recognize injustice wherever it may be.

To be a feminist is not to identify with marginality. It is about creativity in the interstices. To be a feminist is to be in a state of vigilant protest in the mundane.

Feminism is the art of incremental alteration. For this reason, feminism requires not just an attunement to the moment, but most of all, a historical consciousness. We need the perspective of the long view.

Let us remember.

Let us bear witness.

Let us keep going, let us not give up.

Let us be like moss.

Jean P. Tan

November 12, 2018

May 17, 2022