Dear colleagues,

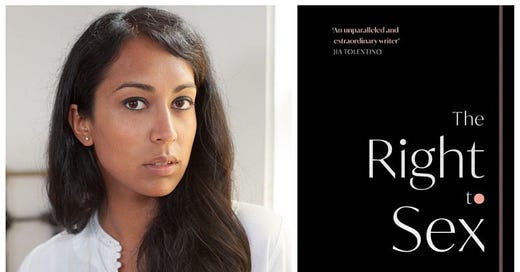

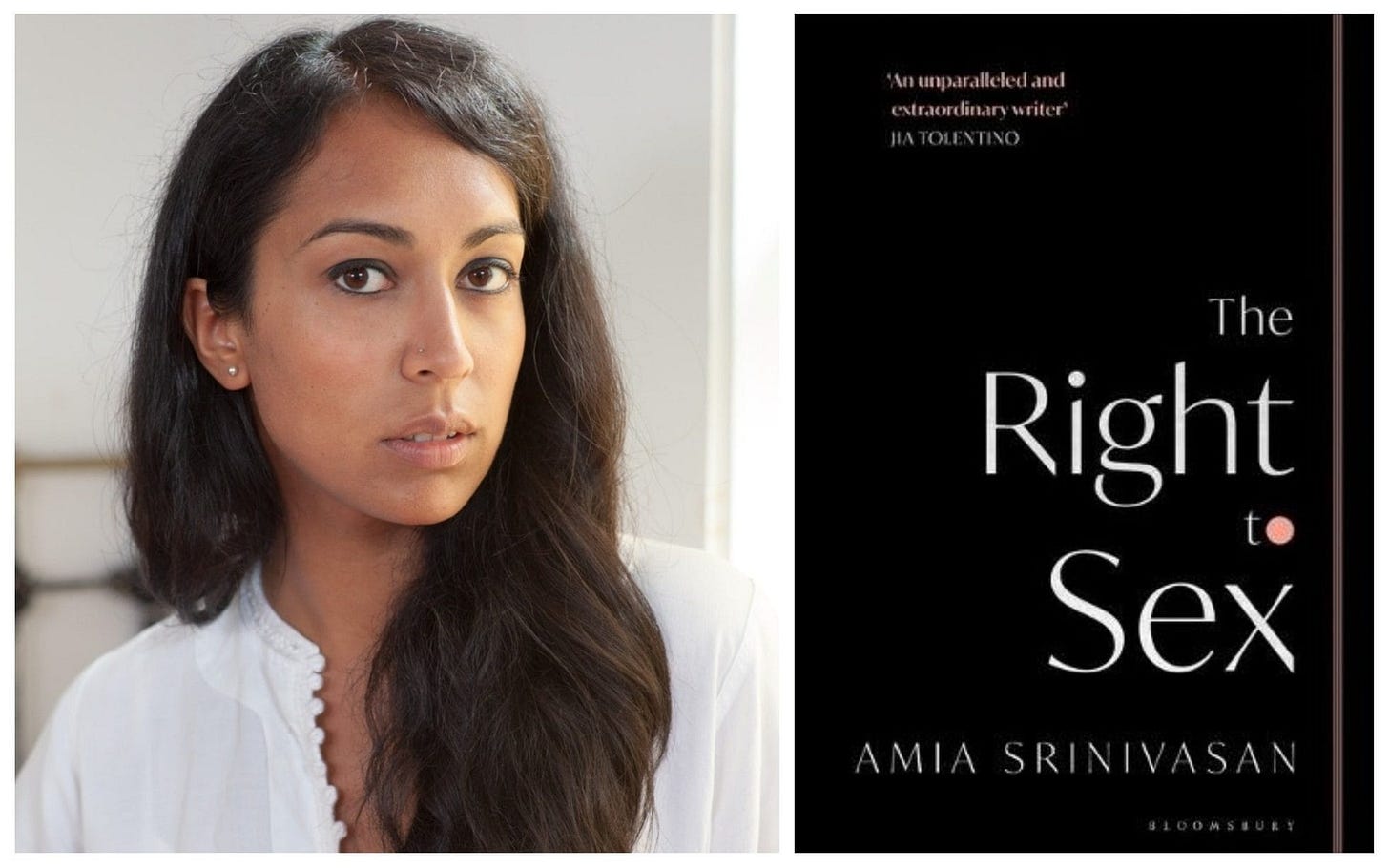

Happy new year! I'm happy to introduce The Right to Sex, the first book by philosopher and public intellectual Amia Srinivasan, formerly a lecturer of philosophy at University College London, and currently Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at All Souls College, Oxford University.

The book is a collection of six accessibly written essays, a few of which have been previously published. In these essays, Srinivasan explores different contemporary questions related to feminism and women’s issues, covering topics such as sexual assault, pornography, and “incel” ideology, and the ways that these are now shaped by 21st century digital technologies.

The common thread across the book is Srinivasan’s attempt to complicate the framing of issues that, she implies, are often oversimplified in public discourse. Reflecting on examples from American and British newspaper headlines, she acknowledges the binary ways that these issues have been framed, and then encourages her readers to see them with fresh eyes. She does this by connecting these examples to broader political and social contexts, or by introducing more complex counter-examples. For example, in the chapter “The Conspiracy Against Men,” after deftly summarizing both the conventional feminist framing of the #Metoo movement as well as the familiar pushback from men who claim they have been victimized by so-called “cancel culture,” she situates these narratives within the more complex political and social realities of the US and the UK (and briefly, within India): race, class and caste, and the history of the disproportionate incarceration of Black men in the US. She ends the chapter by introducing a "gray area" example, the 2014 accusations of sexual assault against Kwadwo Bonsu, a junior at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and she questions whether the structures that have emerged to address sexual violence on campuses can appropriately address cases such as this.

Written by a philosopher ensconced in academia, the issues that Srinivasan raises will resonate with the members of WDP and BTG, because of the familiarity of the university context from and about which she writes. This is evident in some of her chapter titles: “Talking to My Students About Porn,” and “On Not Sleeping With Your Students.” Many WDP members will likely be able to think of parallel examples from their own experiences, of the many university-based examples she gives: the controversial academic conference, the professor with the reputation for sexually harassing his students, the failures of universities to adequately address sexual violence on campus. Srinivasan’s Western and Anglophone context, however, means that there will also be a lot that will seem alien (for example, the free-flowing discussion of pornographic videos in a classroom of sexually active students who speak openly about their sexual practices), or if not alien, then disconnected from the harsher realities experienced by women and girls in the Global South, such as extreme poverty, maternal mortality, human trafficking, the exclusion from formal education, or the vulnerabilties associated with being women migrant workers.

When reading Srinivasan’s book from our standpoint, then, one fruitful way forward might be to bring a Global South perspective to bear on her provocations. And they are, indeed, provocations: this is a book with many questions but few answers. Srinivasan does not offer any novel systematic theorizing to usher in a new way of doing feminist philosophy. Rather, she invites her readers precisely to resist the temptation to settle for easy solutions.

Here are a few questions that I offer, then, as starting points for an engagement with Srinivasan’s work.

In both the first and final essays, Srinivasan reflects on the issue of carcerality. In the first essay, she briefly reflects on carcerality in relation to the problem of sexual assault; in the final essay she ponders on carceral approaches in relation to debates within feminism about how to view sex work. On page 24, Srinivasan asks: “If the aim is not merely to punish male sexual domination but to end it, feminism must address questions that many feminists would rather avoid: whether a carceral approach that systematically harms poor people and people of colour can serve sexual justice….?” What carceral realities in the Philippines are important to bear in mind when exploring answers to this question?

The point of departure for the second chapter is a discussion of the representations in pornography that harm women. The chapter ultimately argues for a kind of “negative” sex education, that ought to have as its aim, arresting the “onslaught” of more speech or more images of sex, to allow young people to imagine “new meanings” of sex, to allow them to “reconfigure their desires” (pp. 70-71). To what extent do you agree with this, and to what extent might this be possible in the Philippine context? Are there cultural resources available to us that might help facilitate such reimagining?

In the essay, “The Right to Sex,” Srinivasan makes references to liberation struggles among the LGBTQ+ community as she portrays sexual desire as a possible catalyst for political change: “In the very best cases … desire can cut against what politics has chosen for us, and choose for itself” (pp. 90-91). In what ways might non-Western/non-Anglophone ways of thinking about queerness, enrich this idea?

In the essay, “On Not Sleeping With Your Students,” Srinivasan argues that “it is precisely because pedagogy was or could be an erotically charged experience that it could be harmful to sexualize it” (p. 147). The theme of Eros is central not only to classical philosophies of education but also to the understanding of Western philosophy itself (cf. Plato). What implication does this have for the pedagogical relationship broadly, and more specifically, the pedagogical relationship within the discipline of philosophy?

When taken as a whole, a theme that runs throughout the book is how the nature of new digital technologies have affected women. The book is mostly silent, however, on how the usage of these digital technologies is itself shaped by global capitalism. (An anti-capitalist critique is introduced only in the final essay, which begins with an exploration of the debates within feminism on prostitution/sex work.) How might a Marxist-inspired critique of 21st century digital technologies enrich or challenge Srinivasan’s arguments throughout the book?

I look forward to a rich discussion when we meet to discuss the book on February 19, 2022, 5-7 pm PHT. Registration link to follow!

All best,

Dr. Rowena Azada-Palacios

Assistant Professor (on leave), Ateneo de Manila University

Senior Lecturer, London Metropolitan University