On Socrates and Tasyo, from Plato through Kofman to Rizal: Reflections on Figures of the Philosopher

Issue no. 37 (Second of two parts)

By Jean P. Tan

This is a revised version of a lecture I delivered last November 2023, upon the invitation of the Senior AB Philosophy Students of the University of Santo Tomas. The seminar was entitled “Footnotes: The Legacy of Ancient Greek Philosophy.” The thoughts I am sharing with you here are more exploratory and suggestive than fully worked out. Where I speak of Sarah Kofman’s ideas, it is more in the manner of an invitation to discover her works, rather than a systematic introduction. And the musings I offer are meant to open lines of inquiry for your consideration, rather than present satisfactorily argued intuitions.

[Editor’s note: The first part of this essay is available here.]

3. Pilosopo Tasyo

Who might stand as a figure (if not the figure) of the philosopher for us the way Socrates has functioned as an icon of the philosopher for Western thought? By “us” I mean practitioners of academic philosophy in the Philippines, for whom the novels of Rizal have a canonical status from both historical and literary standpoints. By “us,” I mean students and teachers of philosophy who have come to philosophy through a colonial education that has its roots in Europe.

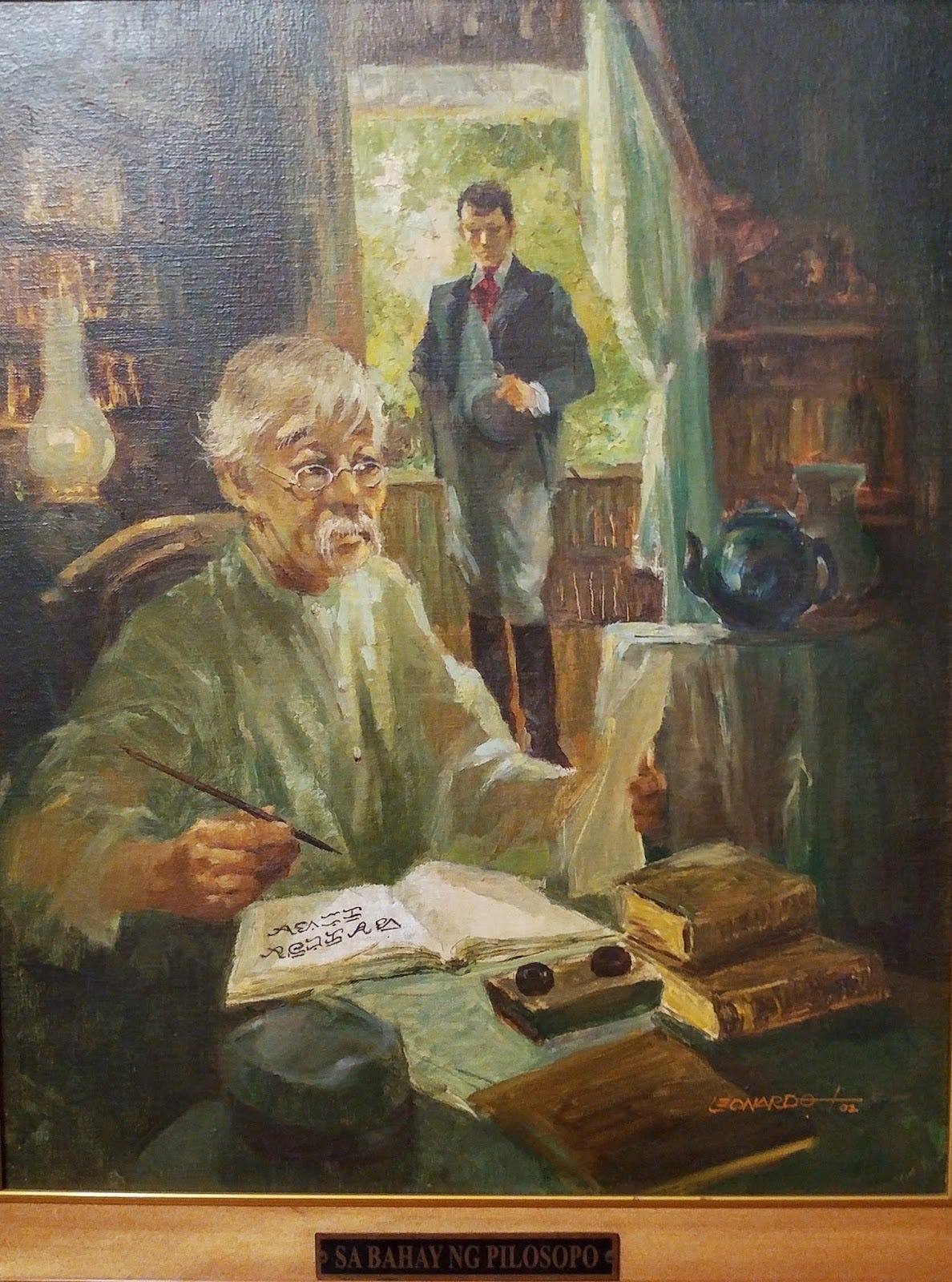

Who is Socrates for us? Do we have accounts to settle with our Socrates? For the final part of this lecture, I suggest that we consider these question through a reading of Rizal’s Pilosopo Tasyo in the 25th chapter of Noli Me Tangere, “In the House of the Philosopher.”1

In her 1982 monograph, The State of Philosophy in the Philippines, Emerita Quito distinguishes two levels of discussion on “philosophy and philosophers” — namely, the “academic” and the “popular or grassroots” levels. For Quito, in the academic level, though there are teachers of philosophy, “there are no real philosophers in the strict sense.” On the other hand, in the grassroots level, she writes,

the term “philosophy” is virtually unknown, but the term ‘pilosopo’ (Pilipino word for “philosopher”) is a pejorative name for anyone who argues lengthily, whether rightly or wrongly. The term alludes to a character called ‘Pilosopo Tasyo’ (Tasyo, the Philosopher) who perorates endlessly in one of the novels of the Philippines’ national hero, Jose Rizal.2

It is curious that in this oft-cited passage, the figure of Pilosopo Tasyo is said to belong to (or originates from) the popular or grassroots conception of philosophy, rather than the academic. In fact, Quito partially attributes to the contamination of the academic consciousness by this popular pejorative conception the lack of esteem in which philosophy is held in the Philippines:

These two levels of philosophy [academic and popular/grassroots] cannot easily be dissociated for the term ‘pilosopo’ has seeped into the academic consciousness with a damaging effect. This is one reason that philosophy has not enjoyed the same prestige in the Philippines that it has in most European countries.3

While Quito mentions Pilosopo Tasyo as an allusion made by popular consciousness, the character Pilosopo Tasyo belongs — if not, strictly speaking, to the academic, then at least –to the “learned” (that is to say, European-educated) class. This suggests that what is at issue in the pejorative use of “pilosopo” might not simply be a distaste for “lengthy arguments” but class conflict and political resistance.

Contrary to Quito’s depiction of Tasyo (or of the presumed popular understanding of Pilosopo Tasyo), Tasyo — at least in Chapter 25 of the Noli — is hardly given to “endless peroration.” He might be inclined to enthusiasm when he started talking about his project of writing Tagalog in hieroglyphics, but even then, he stopped himself short instead of going on and on about it. His speech is measured. He stops to think upon Ibarra’s difficult questions before offering his thoughts. In fact, the first advice he gives Ibarra was for Ibarra to refrain from seeking his advice.

Allow me to quote this excerpt at length. In this chapter, Ibarra visits Pilosopo Tasyo to seek his advice about his plan to establish a school:

[Ibarra:] “I would like to have you advise me as to what persons in the town I must first win over in order to assure the success of the undertaking. You know the inhabitants well, while I have just arrived and am almost a stranger in my own country.”

Old Tasio examined the plans before him with tear-dimmed eyes. “What you are going to do has been my dream, the dream of a poor lunatic!” he exclaimed with emotion. “And now the first thing that I advise you to do is never to come to consult with me.”

The youth gazed at him in surprise.

“Because the sensible people,” he continued with bitter irony, “would take you for a madman also. The people consider madmen those who do not think as they do, so they hold me as such, which I appreciate, because the day in which they think me returned to sanity, they will deprive me of the little liberty that I’ve purchased at the expense of the reputation of being a sane individual. And who knows but they are right? I do not live according to their rules, my principles and ideals are different. The gobernadorcillo enjoys among them the reputation of being a wise man because he learned nothing more than to serve chocolate and to put up with Padre Damaso’s bad humor, so now he is wealthy, he disturbs the petty destinies of his fellow-townsmen, and at times he even talks of justice. ‘That’s a man of talent,’ think the vulgar, ‘look how from nothing he has made himself great!’ But I, I inherited fortune and position, I have studied, and now I am poor, I am not trusted with the most ridiculous office, and all say, ‘He’s a fool! He doesn’t know how to live!’ The curate calls me ‘philosopher’ as a nickname and gives to understand that I am a charlatan who is making a show of what I learned in the higher schools, when that is exactly what benefits me the least. Perhaps I really am the fool and they the wise ones—who can say?”

The old man shook his head as if to drive away that thought, and continued: “The second thing I can advise is that you consult the curate, the gobernadorcillo, and all persons in authority. They will give you bad, stupid, or useless advice, but consultation doesn’t mean compliance, although you should make it appear that you are taking their advice and acting according to it.”

Ibarra reflected a moment before he replied: “The advice is good, but difficult to follow. Couldn’t I go ahead with my idea without a shadow being thrown upon it? Couldn’t a worthy enterprise make its way over everything, since truth doesn’t need to borrow garments from error?”

“Nobody loves the naked truth!” answered the old man. “That is good in theory and practicable in the world of which youth dreams. Here is the schoolmaster, who has struggled in a vacuum; with the enthusiasm of a child, he has sought the good, yet he has won only jests and laughter. You have said that you are a stranger in your own country, and I believe it. The very first day you arrived you began by wounding the vanity of a priest who is regarded by the people as a saint, and as a sage among his fellows. God grant that such a misstep may not have already determined your future!”

We could say that Tasyo and Ibarra are doubles of each other. Ibarra’s recklessness (courage?) and youthful enthusiasm find their mirror image in the caution and prudence of Tasyo. Rather than faith in the power of truth (“… truth doesn’t need to borrow garments from error”), wisdom for Tasyo is prudence wrought by disillusionment: “Nobody loves the naked truth.”

Socrates disavows knowledge; Tasyo cloaks himself in lunacy. He chooses to bide his time, to live in hiding, writing in hieroglyphics in order not to be understood, writing for a future with script that he himself has to invent. Tasyo’s irony is decidedly of the bitter kind, more Nietzschean in temperament than Socratic.

What does it mean to have Tasyo as our figure of the philosopher? What does it mean that the philosopher chooses to take refuge in dissimulation, choosing the reputation of a madman in order to preserve his liberty, “the little liberty” that his social and political situation permits him?

What does it mean to settle our accounts with Pilosopo Tasyo? I think it would mean recognizing the fact that the conception of the philosopher as embodied by Tasyo is decidedly political in nature. What is at stake in Tasyo’s and Ibarra’s wrestling with truth is nothing short of life and freedom. Tasyo is not Socrates, a citizen of the Athenean polis, who till the very end was granted the freedom to choose between exile and death. Tasyo is the figure of the philosopher as a colonial subject.

Whereas Socrates, denying that he possesses wisdom, nevertheless identifies with the status of philosopher – friend of wisdom – and is called philosopher by his friends, students, admirers, Tasyo is branded “philosopher” as an insult by a detractor, the curate – a colonial authority: “The curate calls me ‘philosopher’ as a nickname and gives to understand that I am a charlatan who is making a show of what I learned in the higher schools….” Is it any wonder then that until now, the term “pilosopo” still rings with the tone of mockery?

I propose that Noli’s 25th chapter, “In the House of the Philosopher,” should be read as a metaphilosophical reflection — and in true Platonic fashion, in dialogue form — about the aporia of philosophy as practiced in the shadow of coloniality: Pilosopo Tasyo’s metaphor about Ibarra’s plans for building a school, transplanted from a foreign soil, lacking in support from the native ground, could very well be an invitation for us to take stock of the colonial presuppositions of our philosophical traditions:

[Tasyo:] “There you see that gigantic kupang, which majestically waves its light foliage wherein the eagle builds his nest. I brought it from the forest as a weak sapling and braced its stem for months with slender pieces of bamboo. If I had transplanted it large and full of life, it is certain that it would not have lived here, for the wind would have thrown it down before its roots could have fixed themselves in the soil, before it could have become accustomed to its surroundings, and before it could have secured sufficient nourishment for its size and height. So you, transplanted from Europe to this stony soil, may end, if you do not seek support and do not humble yourself. You are among evil conditions, alone, elevated, the ground shakes, the sky presages a storm, and the top of your family tree has shown that it draws the thunderbolt. It is not courage, but foolhardiness, to fight alone against all that exists. No one censures the pilot who makes for a port at the first gust of the whirlwind. To stoop as the bullet passes is not cowardly—it is worse to defy it only to fall, never to rise again.”

Listening to Pilosopo Tasyo in the 21st century, and adjusting his metaphor to our purposes, shouldn’t we be able to confront and question his assumption that philosophy is “transplanted from Europe to this stony soil”? To settle our accounts with Pilosopo Tasyo, we have to confront the discomfiting reality that for many of us academic philosophers, we are like Ibarra who admits that he is “almost a stranger in my own country.”

Perhaps it is not, as Quito thinks, the propensity for “lengthy arguments” that have earned us philosophers the derision of our fellow Filipinos, but the fact that we have been and continue to be “weak transplanted saplings” still struggling to deepen our rootedness in our own soil.

4. Postscripts

We come back full circle to the meta-philosophical questions I initially raised about our practices in philosophy: With whom do we speak? In what languages? To whom do we write? For whom do we publish? With whom do we engage in our conversations? Whom do we exclude, marginalize, or instrumentalize? Under what conditions of power or powerlessness do we philosophize in our time?

As a woman philosopher, I still have other scores to settle with Socrates and Tasyo both — but that is a topic for another essay.

1 Jose Rizal, Noli Me Tangere (Berlin, 1887). Translated by Charles Derbyshire. All passages from Noli Me Tangere were accessed through www.kapitbisig.com.

2 Emerita Quito, The State of Philosophy in the Philippines (Manila: De La Salle University, 1983), 9.

3 Ibid., 9-10.