Katarúngan at pakikibáka in epistemic discourses: A commentary on Dr. Jacklyn Cleofas's “An Account of Justice as a Virtue from Katarúngan”

BTG issue no. 42

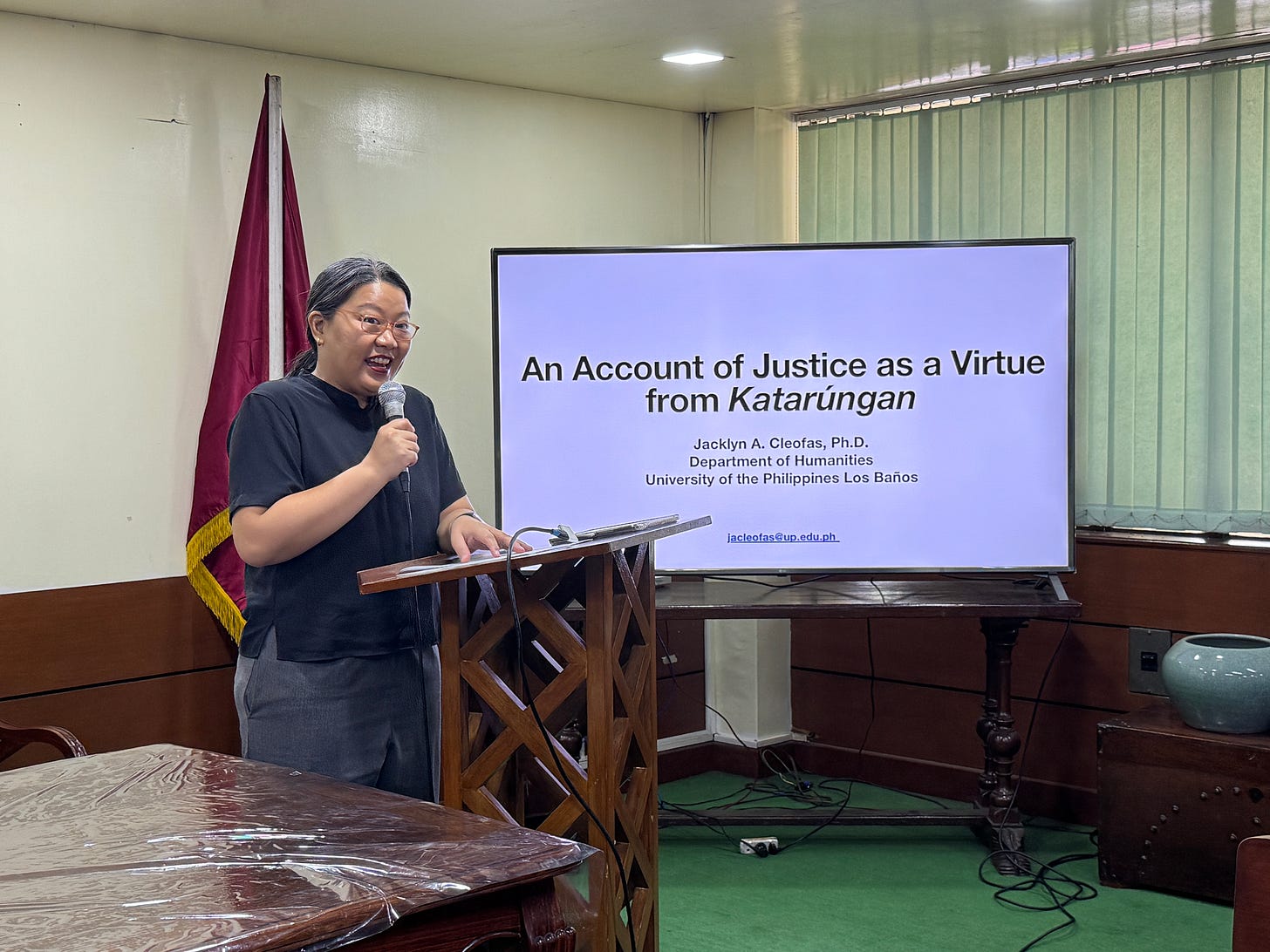

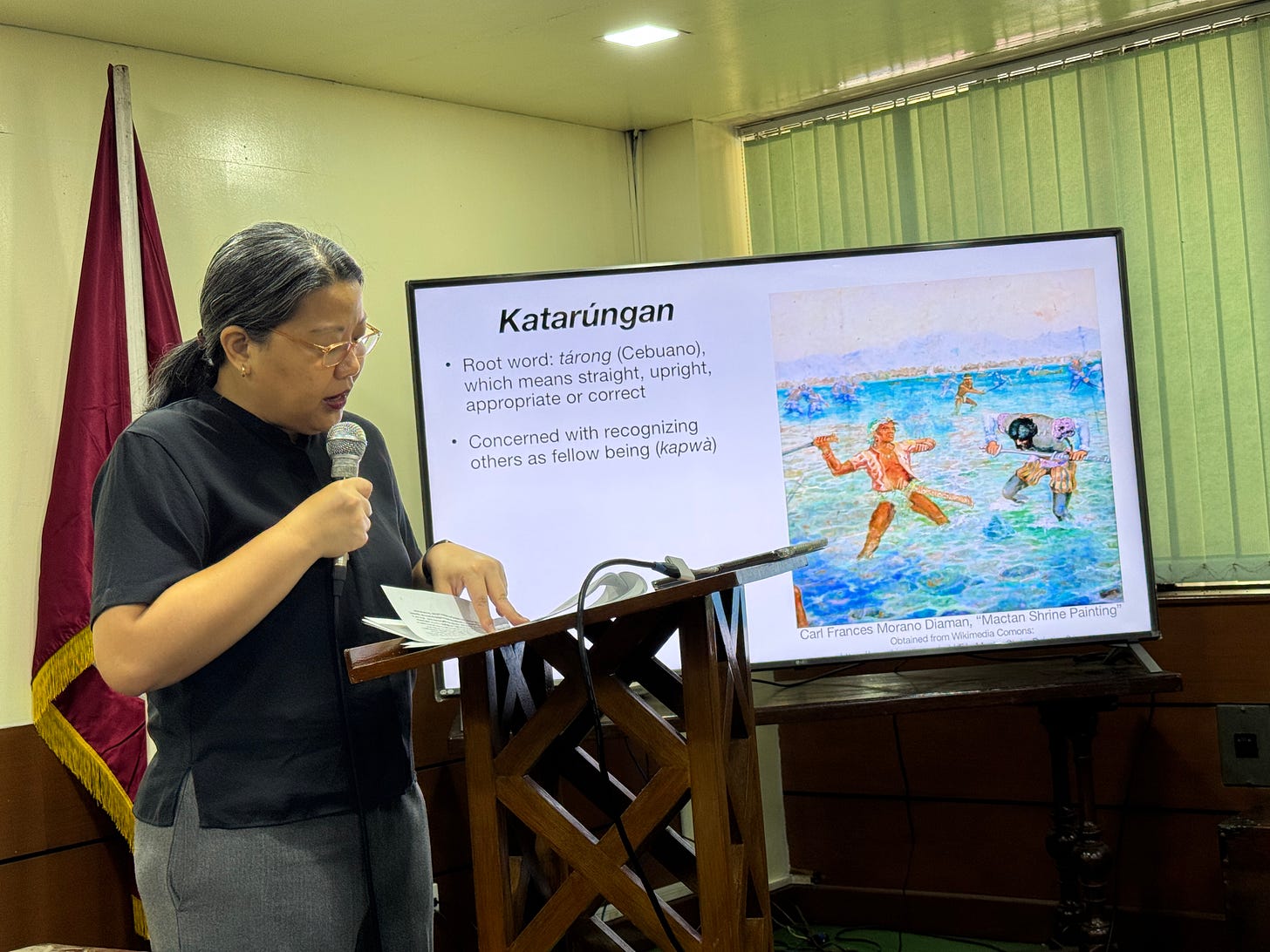

Editor’s note: In this issue of our newsletter, we are pleased to feature Joyce Fungo’s insightful commentary on the lecture delivered by Dr. Jacklyn Cleofas during our recent Beyond the Ghetto event at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines. This special occasion marked our 27th lecture and only the third in-person gathering since the founding of BTG, made even more meaningful by the generous hospitality of Chief Chloe Piamonte and the Center for Social Inclusivity Studies. Dr. Cleofas’s lecture launched our new series, “Filipino Philosophy: New Directions,” which seeks to broaden the scope of what counts as Filipino philosophy by centering lived realities, care, justice, and inclusion. Joyce’s commentary thoughtfully engages with these themes and includes quotes from Dr. Cleofas’s unpublished manuscript. We are also delighted to share photos from the event, capturing the spirit of collaboration and critical dialogue that made the day so memorable.

Below is the abstract of Dr. Cleofas’s paper:

An Account of Justice as a Virtue from Katarúngan

Jacklyn A. Cleofas

University of the Philippines Los Baños

In this paper, I offer a new account of justice as a virtue under the Capabilities Approach (CA) that is also informed by one Filipino term for justice. Katarúngan resonates with the Capabilities Approach (CA) in that it is also (a) more relational than standard Western approaches, (b) comparative and focuses on what can be realized, and (c) puts an emphasis on saving the worst off. I show that these resonant perspectives lead to an understanding of justice as a disposition to reduce and remove shortfalls in well-being freedom or capabilities; more specifically, in a way that promotes solidarity. The element of solidarity in this account is rooted in the notion of kapwâ (fellow being), which neatly dovetails with the feminist idea that effective resistance against oppression requires a kind of solidarity that is transformational. Because transformational solidarity requires sensitivity to differences in class, gender, and privilege, those who are cultivating the virtue of justice can deploy a capabilitarian approach that avoids greater emphasis on monolithic or hegemonic institutional action. What ensues is a form of acting justly that operates at the grassroots level and challenges enduring states of affairs that systematically enable or allow capability shortfalls. Toward the end of the paper, I discuss how the account of justice can be applied to cases in the Philippines where culturally rooted conciliatory approaches are injudiciously utilized to deal with instances of violence against women such as rape.

By Joyce Fungo

De La Salle University-Manila and Polytechnic University of the Philippines

Preliminaries

Thank you, Dr. Cleofas, for being generous with your time and for bringing this new account of justice as virtue to the PUP x WDP audience. I believe I speak for all of us here when I say that it is a pleasure to have you speak to us about your work.

My training is specifically in epistemology, and I am hoping that a conversation between some issues within political epistemology and this account of justice that Dr. Cleofas offers may be of value. Let me begin by noting a few things I really appreciated from the talk:

First, I was quite fascinated by the paper’s methodology: informing the capabilities approach (CA) – an already widely embraced framework for political philosophy – with the important Filipino conceptual resource of katarúngan. I don’t suppose that I would be the only participant here who was so happy seeing everyday Filipino language terms utilised in a way that reveals a shared conception of justice – one that is refreshingly devoid of colonial baggage – and one that makes sense in relation to many other Filipino concepts that are already embedded in our everyday practices (such concepts as kapwâ, waláng kapwâ, pakikibáka, etc. ). Whenever this happens, I almost get a cognitive dissonance of sorts – as if two of my worlds are colliding (my native language and technical philosophical parlance). When I think of ‘justice’ pre-theoretically, the impression I get is that it is this floating concept that stands “before the bar of impersonal truth”, to borrow a phrase from Margaret Urban Walker’s Moral Understandings (p. 20). I think this speaks to a much broader concern that we have of standard Western conceptions of justice – where justice is removed from relationality in pursuit of ideals that would have subjects’ life histories and social positionalities be only of secondary importance. My impression of justice (the English term) is almost always in reference to some Platonic ideal, whereas my impression of katarúngan is quite contrary to the English term justice. I think of katarúngan as how a character from a Filipino soap opera would say it – it always seems personal and relational and usually arises out of some pain, rage, or fierce indignation. As it turns out, neither of these pre-theoretical impressions quite captures the relevant conceptual genealogies drawn by Dr. Cleofas in her work, and this insight now shifts my understanding of katarúngan.

Second, I especially appreciate the theoretical virtues that underlie this new account of justice, namely, that it is realisable, critical, and nuanced.

1. This account of justice is realizable. Dr. Cleofas makes it a point to show that we do not simply talk about justice as if we are fantasizing about it – it has to be something that we can realise. Importantly, I believe this relates to a budding trend now in philosophy where Charles Mills’s Ideal Theory as Ideology is starting to gain traction – I believe, rightfully – as opposed to Rawlsian-style theories of justice that rely on all agents fully participating in upholding principles of justice, later rendered by Mills to be perniciously idealistic.

2. This account of justice is critical. Dr. Cleofas emphasizes the relationality of katarúngan, and the theoretical virtue I’d like to emphasize here is that we check for blind spots that prior canonical theories may have missed. It is critical of standard theories of justice that fail to incorporate human relations.

3. This account of justice is nuanced. Dr. Cleofas also ensures that in the process of heralding non-Western, and more specifically of Filipino, concepts and practices, we do not rely on a simple, black-and-white analysis of such ideas. This is quite evident throughout the work, but it particularly resonated with me when she talked about the disruption of social harmony and Katarúngang Pambarangay, i.e., an alternative judicial system that is widely used in the Philippines. Additionally, while there are virtuous things to be taken from katurangan, for instance, or pakikibáka, we also have to be vocal about features within these ideas that must be rethought.

Third, I really appreciate how accessible the material is. I was fortunate enough to have seen the work in written format, and I marvel at how accessible the writing is. It is palatable to someone such as myself, for instance, who is not attuned to political philosophy terminology.

Now, I’d like to pose two questions for us to ponder:

Pakikibáka and epistemic obligations for resistance and protest

One of the things that intrigued me about Dr. Cleofas’s work is her discussion of solidarity, where she talks about the consistency of “the feminist solidarity conception of justice” with the Filipino concept of “pakikibáka, or the aspect of relating with fellow beings associated with collective resistance against oppression.” (p. 19) Just this definition being intricately tied with the notion of kapwa already departs from more premature notions of collective resistance. The ‘collective’ here, to me, implies more than just members of a group coming together to resist or to protest – on the contrary, it is a gathering that commences with a more interpersonal sense of togetherness, and they come together with the purpose of expressing solidarity. In this light, I am wondering how pakikibáka as collective resistance encounters ‘epistemic obligations in protest’ as outlined by Jose Medina in his book, Epistemology of Protest.

I am thinking specifically of safeguards against disingenuous protests, e.g., performative activism, bad faith counter-protests (e.g., Blue Lives Matter in response to Black Lives Matter). I wonder whether the proposed account of justice as virtue, while it allows—perhaps, even encourages—activism, has mechanisms to discourage disingenuous protests. In other words, would this account of justice as a virtue have space for such epistemic obligations?

Extending this account of justice into epistemic injustice scholarship

Finally, I would like to share my musings about a possible extension of the idea of katarúngan as it was rendered here onto epistemic injustice scholarship. According to Dr. Cleofas, under a capabilitarian approach,

[i]njustice is expressed in terms of capability inequality. According to Drydyk, the relevant inequalities are those that make it difficult or impossible for certain individuals or groups to live lives worthy of human dignity. In the context of the examples already given, this could mean insufficient access to health care and lucrative job opportunities, or different levels of access to scientific or artistic training for members of various nationalities, genders, socio-economic groups, etc. Deploying CA then requires that we maintain everyone’s capabilities well beyond the minimum standard of survival.

How might we inform epistemic injustice scholarship by means of the CA + katarúngan framework? Epistemic injustice is, of course, an injustice. But it is a peculiar kind of injustice. In the first place, it is almost unmappable within any existing legal context (unlike the sorts of injustice that are under scrutiny in the case studies considered by Dr. Cleofas in her paper). There are really no legal repercussions for ascribing the wrong degree of credibility to a knower.

What would be the capabilities in question here, I wonder. What freedoms are at stake? An insufficient access to the credibility economy? Constraint on one’s freedom to speak and be heard, to be listened to, to be perceived as a knower?

These are questions for me to ponder – and perhaps also gain Dr. Cleofas’s insight into them. I do not demand answers, but I look forward to a fruitful discussion.

Cited Works

Cleofas, Jacklyn A. “An Account of Justice as a Virtue from Katarúngan” (Unpublished manuscript).

Medina, J. (2023). The Epistemology of Protest: Silencing, Epistemic Activism, and the Communicative Life of Resistance. Oxford University Press.

Mills, C. W. (2005). Ideal theory as ideology. Hypatia, 20(3), 165–184.

Walker, M. U. (2007). Moral understandings: A feminist study in ethics (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.